What is the economic impact of the H-1B visa program?

Understanding the impact of skilled immigration on wages, employment, and productivity

Table of Contents

Introduction

‘Twas the night before Christmas, and all through X,

Discourse was unfolding like a massive trainwreck!

The tweets were all posted with fiery despair,

In hopes that their hot takes would trend everywhere.

The news had been dropped with a government seal—

Sriram was in, and the rage became real.

When what to my cynical eyes should appear,

But think pieces flying from far and from near.

"He's globalist! Elitist! A tech overlord!"

"A puppet! A shill! This must be ignored!"

"Why should an immigrant get such a prize?"

The nativists declared with furor in their eyes.

Then counter-takes flew, just as hot, just as bright—

"H-1Bs built this! You’re mad we took flight?"

"Tech runs on talent, Elon’s damn right!"

The centrists arrived, all measured and neat,

With "Both sides are right!" in their usual tweet.

And as journalists rushed to collect every thread,

X burned like Rome while the discourse was fed.

So next time a headline stirs up a fight,

Just touch grass and chill—it’ll change overnight.

But if you must post, do know what’s in store:

A never-ending cycle of discourse and war.

- ChatGPT

While X can hardly be considered a representative sample of the American public, I think it’s quite safe to say that the H-1B visa program has come under intense scrutiny in the past several weeks.

And while it would be tempting to write off such scrutiny as the byproduct of racism against Indian immigrants, I think that such a dismissal would be lazy - it would represent an attempt to poison the well against one’s ideological adversaries without dealing with their more substantive arguments about the economic impact of the H-1B program. Bearing this in mind then, let’s do exactly the opposite: let’s actually discuss the substantive economic impact of the H-1B program!

Now technically speaking, the term “economic impact” covers a broad range of activities - employment, trade, productivity, debt, inequality, growth, wages, and more! Because I have little interest in writing a Tolstoy-length novel about immigration (and the National Academies might as well have already done that), I’ll primarily focus on answering the 3 economic questions most relevant to the H-1B debate:

Does the H-1B visa program decrease the employment of native (US-born) workers?

Does the H-1B visa program decrease the wages earned by native (US-born) workers?

Does the H-1B visa program increase the productivity of US firms?

Let’s dive in!

The H-1B Visa 101

Disclaimer: This section is as dry as the Sahara desert🏜️. However, I would strongly recommend not skipping it because if you do not understand how the H-1B visa process works, you will not be able to understand its strengths and weaknesses.

Before we can analyze the economic impact of the H-1B program, we must first understand exactly what an H-1B visa is and how one goes about obtaining it. Acquiring this information is complicated, however, because the program has undergone several substantial changes since its inception in 1990. To keep things as simple as possible, I’ll focus on the H-1B program during fiscal years (FY) 2006-2020 as this is the time period most relevant to the studies we’ll be reviewing later in this article.

What Is The H-1B Visa?

The H-1B visa is dual-intent visa sponsored by employers who wish to hire foreigners in occupations which require at least a bachelor’s degree.1 The visa lasts up to 3 years and may be renewed for an additional 3 years (Department of Labor 2020). After this 6-year period has been exhausted, the visa can be extended in 1-year increments if the visa holder is in the process of obtaining permanent residence (USCIS 2024a).

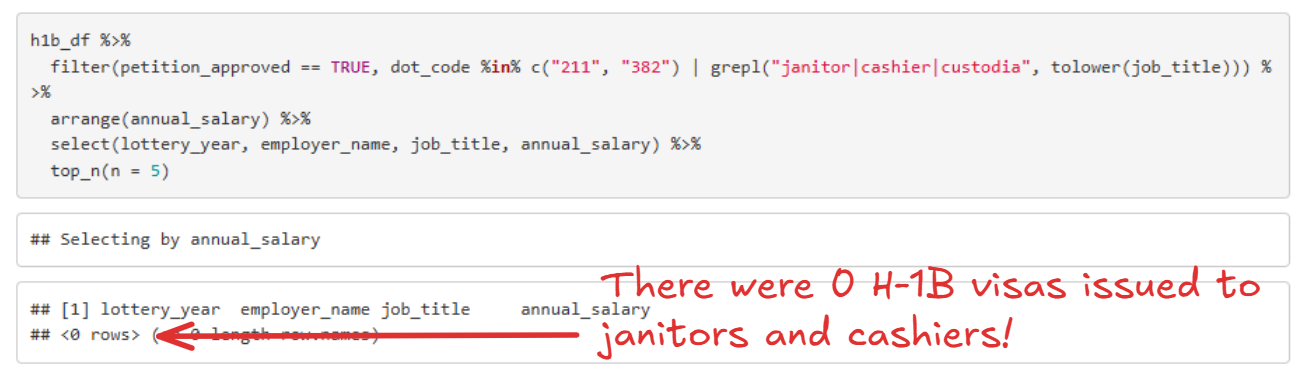

Importantly, because the H-1B visa requires the job in question to be at the level of a bachelor’s degree or higher, claims that “janitors” and “cashiers” are obtaining H-1B visas are highly dubious.

These claims are not based on actual visas being issued, but rather Labor Condition Applications (LCAs), a term which is explained in the next section. Consequently, when one attempts to verify whether such applications have actually been granted H-1B visas via the H-1B lottery, no such visas can be found …2

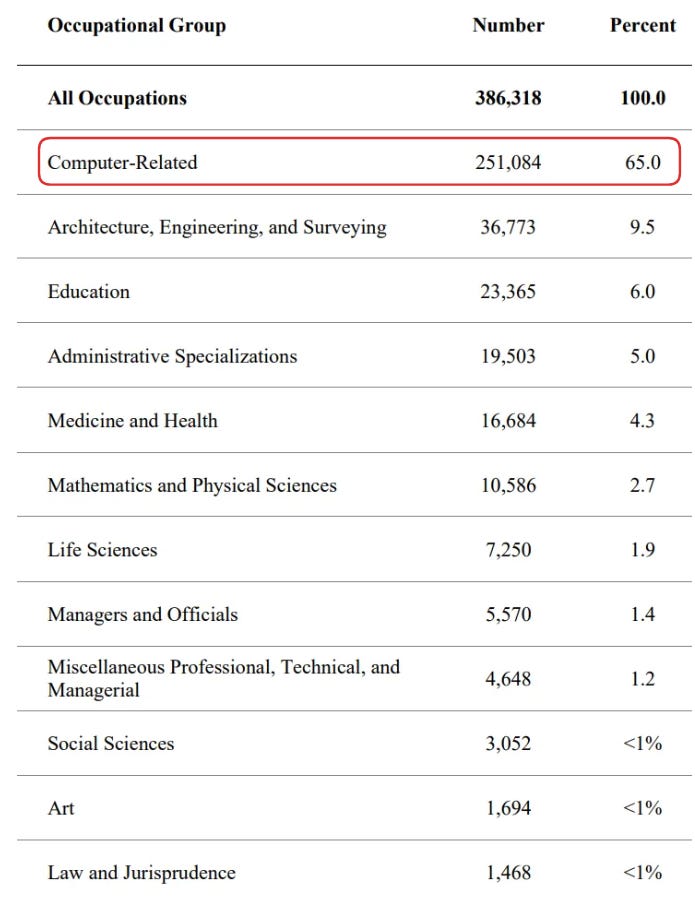

… and the majority of approved H-1B visas are issued to individuals in computer-related occupations.

The Labor Condition Application

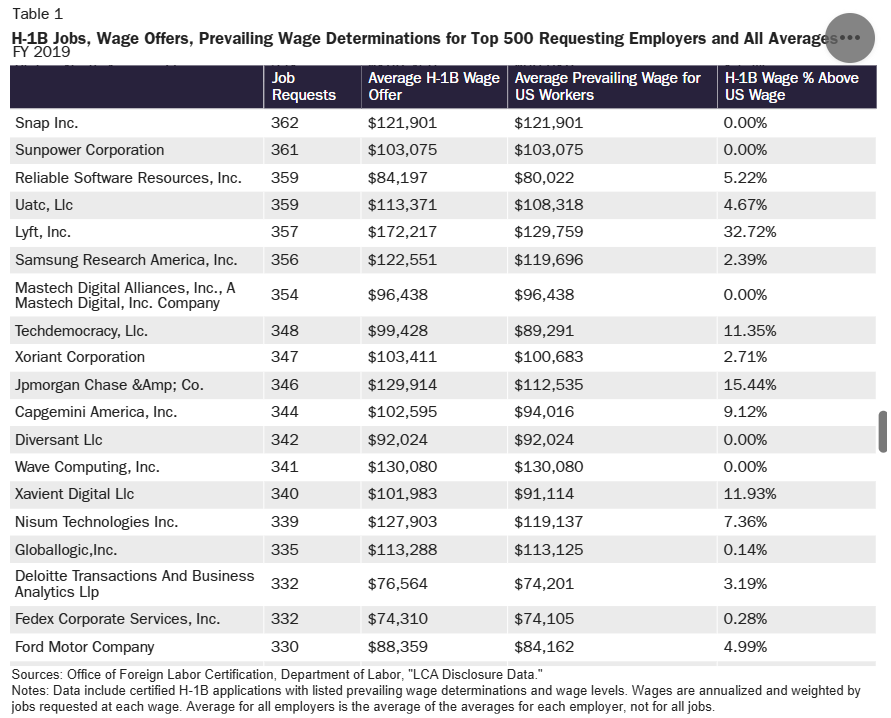

During FY 2006-2020, the first step in the H-1B process was to submit a Labor Condition Application (LCA). The LCA requires the employer to attest that the visa applicant will not adversely impact the conditions of other workers “similarly employed” at the company …

and that the applicant be paid the higher of the actual wage and prevailing wage associated with the position in question.3

What exactly are these “actual” and “prevailing” wages? Well …

The actual wage is “the wage rate paid by the employer to all individuals with experience and qualifications similar to the H-1B nonimmigrant’s … for the specific [job] in question … If there are no similarly employed workers [at the workplace in question], the actual wage is the wage paid to the H-1B worker.”

The prevailing wage for non-union workers is “the weighted average of wages paid to similarly employed workers (i.e., workers having substantially comparable jobs in the occupational classification) in the geographic area of employment.”

The prevailing wage can be determined using the following 3-step process:

Identify the occupational code that most closely resembles the job in question.

Identify the skill level of the job in question on a scale of 1-4 where 1 is entry-level and 4 is highly-experienced.

Use a pre-approved salary dataset (e.g. Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics - OES) to estimate the wage corresponding to the skill level of the job in the relevant geographic area.

Nice (2017) provides a nice example (pun intended) of this process in action:

The four prevailing wage levels for Accountants and Auditors in Washington, D.C. … [during FY 2018] are:

Level 1: $56,971 per year

Level 2: $74,048 per year

Level 3: $91,104 per year

Level 4: $108,181 per year

Once the employer submits the LCA, the Department of Labor can certify it, so that the application can proceed to the next step.

Note that LCAs may also be filed when H-1B visa holders wish to:

Renew their visa.

Transfer their visa to a different place of employment.

Amend the conditions of their employment.

Thus, any study of H-1B visas which does not disaggregate different types of LCAs will yield inaccurate results!

The I-129 Petition

In addition to the LCA, the employer must submit an I-129 petition on behalf of the H-1B visa applicant. Employers are obligated to pay multiple fees in this process such as:

The standard filing fee or a considerably more expensive premium processing fee.

A $500 anti-fraud fee (USCIS 2020).

A $1.5k ACWIA fee designed to build up technical skills in the existing domestic workforce (USCIS 2017).4

Submitted I-129 petitions are then entered into the H-1B lottery.

The Lotteries

In years when the # of submitted petitions exceeds the statutory visa caps, US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) conducts a random lottery - or rather two random lotteries to distribute visas: the Regular Cap (RC) lottery and the Advanced Degree Exemption (ADE) lottery (Department of Homeland Security 2019).

The RC lottery is used to distribute 65k visas to skilled workers regardless of degree level. In other words, success in the RC lottery does not depend on whether one has a bachelor’s vs graduate degree. Note that a small percentage of these visas are reserved for Singaporean and Chilean applicants via the H-1B1 visa program. This quota is a known advantage that arose as a result of free trade agreements between the US and the aforementioned countries (Office of the United States Trade Representative 2003).

The ADE lottery is used to distribute 20k visas to skilled workers with a graduate degree obtained in the United States. Importantly, this means that US advanced degree-holders have two chances to win the H-1B visa lottery: the RC lottery and the ADE lottery (if they don’t already win in the RC lottery).

Once the I-129 petition is selected in the lottery and is given the rubber stamp by USCIS, the applicant can be granted an H-1B visa!

Importantly, not all submitted I-129 petitions are entered in the lottery. For example, petitions submitted by academia, non-profits, and the government are “cap-exempt” and thus, need not abide by the visa caps that for-profit companies are subject to (Berkeley International Office 2024).

The Present Day

It’s worth reiterating that the process I’ve described above no longer resembles the H-1B process of today. In particular:

The H-1B lottery now precedes the submission of the LCA and I-129 petition. Applicants may now enter the lottery via a simple registration process, and only winners need to submit the LCA and petition (Department of Homeland Security 2019). Importantly, however, it remains the case that a certified LCA does not equate to an issued visa. Lottery-selected petitions may still be denied if, for example, USCIS observes that the occupation in question does not require a bachelor’s degree.

The ADE lottery now follows the RC lottery. This change was implemented to maximize the # of advanced degree applicants securing H-1B visas (Department of Homeland Security 2019).

The H-1B processing fees have increased considerably. For example, the standard filing fee increased to $780 while the premium processing fee increased to $2.8k. Additionally, USCIS introduced a $600 asylum processing fee designed to cover the cost of processing asylum applications. Lastly, USCIS intends to increase the cost of lottery registration to $215 (Department of Homeland Security 2024).5

However (once again), I’ve chosen to describe the older lottery process as it is most relevant to the studies that claim to analyze the economic impact of the H-1B visa program. Speaking of which …

Establishing Causality

How exactly does one estimate the causal economic impact of the H-1B visa program? Broadly speaking, there are two strategies which I consider to be useful.

Lottery Studies

The first type of causally-informative study is the lottery study. By randomly determining which applicants receive a visa, the H-1B lottery randomly causes certain firms to be given a larger # of H-1B workers than others. To estimate the causal impact of the H-1B program then, all one needs to do is simply compare the outcomes of firms with a randomly higher win rate in the lottery to the outcomes of firms with a randomly lower win rate in the lottery.

In this way, the lottery study is basically like a dose-response randomized controlled trial (i.e. each arm in the trial randomly receives a varying dosage of the treatment in question)! There are, however, 5 primary challenges with lottery studies.

1. Confounding by Lottery Type:

Because the H-1B lottery consists of two lotteries - the RC and ADE lotteries - one firm may have a higher win rate than another not due to random chance but instead because they had a higher share of applicants with an advanced degree obtained in the US. While the obvious solution to this problem is to just control for lottery type, USCIS data often does not report which lottery each application was entered into (Dimmock, Huang, and Weisbenner 2022). Thus, a common workaround is to control for proxies of advanced degrees that are available in USCIS data.

2. The Denominator Problem:

For the FY 2006-2020 lotteries, the lottery win rate for a given firm f can be calculated like so:

However, USCIS has not always tracked the denominator in this formula because they returned unselected I-129 petitions unopened to the sender (Mahajan et al 2024). Consequently, researchers have instead attempted to proxy the total # of lottery-subject petitions submitted by each firm using LCA filings. While this workaround is understandable, one must be very careful to exclude non-lottery LCA filings (e.g. renewals, transfers, amendments) lest they risk artificially decreasing the estimated win rate.6

3. The Law of Large Numbers:

The Law of Large Numbers (LLN) states that “the average of the results obtained from a large number of independent random samples converges to the true value, if it exists.” For example, if you flip a fair coin enough times, heads should appear 50% of the time.

What does this have to do with lottery studies? Well, lottery studies only work because the visa lottery creates sizable random variation in each firm’s win rate (e.g. 50% of Firm A’s lottery-subject petitions are selected while 10% of Firm B’s lottery-subject petitions are selected). However, if we’re interested in the behavior of firms which submit a large # of H-1B visa petitions in a given year, the LLN implies that the win rates of these firms should be roughly around the same value (e.g. Firm A wins 33% of its petitions and Firm B wins 27% of its petitions).

With less variation in each firm’s win rate, it becomes harder to discern whether differences in outcomes between firms are driven by the H-1B program or are simply random noise. Thus, lottery studies are less able to make precise causal statements about the impact of the H-1B program in large firms.

4. Generalizability

Unfortunately, none of the currently published studies analyzing the H-1B lottery use data from the new lottery process introduced in FY2021. Thus, the causal impacts estimated by these studies likely would not generalize to certain recent years when the lottery was flooded with fraudulent applications as a result of the new system (see the linked article for additional context).

It’s also worth pointing out that the FY2006 & 2007 lotteries were markedly distinct from subsequent visa lotteries. These lotteries were only used to distribute visas to a subset of visa applicants (namely, those who applied quite late into the process), and as a result, they do not capture the entire causal impact of the H-1B program in a given year.

5. Second-Order Outcomes

Lottery studies are unable to analyze second-order outcomes of the H-1B program. For example, one way the H-1B program might positively impact the economy is via entrepreneurship (think Mike Krieger founding Instagram). However, because the lottery study only compares the outcomes of the initial firms at which H-1B workers are employed, it would never be able to capture the entrepreneurial impact of such workers. This limitation also extends to other second-order outcomes such as the long-run economic impact of the children of H-1B workers.

Cap Change Studies

The second type of causally-informative study is the cap change study. This study quantifies the economic impact of decreasing/increasing the # of H-1B cap by exploiting the fact that the H-1B cap has shifted dramatically over time:

Researchers can quantify the impact of the cap change on cap-subject firms using a statistical method known as difference-in-differences. The basic procedure is as follows:

Estimate the difference in the outcome of interest (e.g. native employment) between the cap-subject firms (e.g. for-profits) and cap-exempt firms (e.g. non-profits) in the years following the cap change.

Estimate the difference in the outcome of interest (e.g. native employment) between the cap-subject firms (e.g. for-profits) and cap-exempt firms (e.g. non-profits) in the years preceding the cap change.

Estimate the difference between (1) and (2). This “difference-in-differences” quantifies the causal impact of the cap change on the outcome of interest in cap-subject firms.

This procedure can be visualized like so:

The intuition behind the approach is that, because the cap change does not impact cap-exempt organizations, we can treat these organizations like a control group that can then be used to estimate the causal impact of changing the cap.

There are, however, 2 primary challenges with cap change studies:

1. Parallel Trends

Critical to the cap change approach is the assumption of parallel trends: namely, that had the cap change not taken place, the cap-subject and cap-exempt organizations would have continued tracking each other in parallel. This assumption can be violated in two ways.

Confounding Shocks: If an additional policy change took place during the same year of the cap change and that policy also had a differential impact on cap-subject vs cap-exempt firms, then the assumption of parallel trends is violated.

Pre-Trends: If the cap-subject and cap-exempt firms were already not trending in parallel prior to the cap change, then the parallel trends assumption is violated.

2. Contaminated Control

In response to a cap change, prospective foreign workers may change their job search behavior. For example, such workers may choose to “settle for academia” in response to a more restrictive cap on the # of H-1B workers at for-profit firms, causing both our intervention group (cap-subject firms) and our control group (cap-exempt firms) to be impacted by the policy change.

This “contamination” of the control group leads the difference-in-differences approach to effectively double-count the impact of H-1B workers on the outcome of interest. (i.e. the estimated impact now includes the impact of H-1B on cap-subject firms and cap-exempt firms).

A Bayesian Approach

Now that we have an understanding of the causal methods, I will describe my approach to tackling our 3 key subjects of interest - the impact of the H-1B visa program on native employment, native wages, and productivity.

My answers to these questions will have a Bayesian structure. I will begin by describing the prior - the judgment we ought to have prior to examining the causal evidence - from both the pro-H-1B and anti-H-1B perspective. Note that these priors will sound opinionated (and arguably biased), and that is fully my intention: I want to clearly capture the sentiments expressed by the various camps in this debate.

Following the discussion of the possible priors one could have, I will then describe the causal evidence which can be used to form a posterior judgment on the question of interest. Let’s begin!

Native Employment

What is the anti-H-1B prior?❌

Multiple independent sources confirm that we are currently in a tech jobs recession:

Indeed has reported that software development job postings are down 30% relative to a pre-pandemic baseline of February 2020.

The payroll company ADP has reported that software development employment is down 20% relative to a pre-pandemic baseline of January 2018.

LinkedIn has reported that hiring in product management and IT have decreased by 23% and 27%, respectively, relative to a pre-pandemic baseline of August 2018.

These statistical trends are also confirmed by accounts on the ground from individuals who could hardly be dismissed as virulent anti-immigrant racists.

Given that such jobs are in short sight, it stands to reason that opening up applications to immigrants will necessarily displace existing domestic workers.

To add insult to injury, we have ample evidence that tech companies openly discriminate against native workers in favor of foreign workers presumably because the latter group is more easily exploited (as we shall see in the next section on wages). For example:

Lambert and Akinlade (2019) conducted a correspondence audit in which 324 resumes were sent to tech employers in Palo Alto. These resumes were identical except that some included a statement indicating that the resume belonged to an F-1 visa holder (i.e. a student visa) and some denoted membership in a cultural club (e.g. Stanford Indian Association). They find that Indian non-citizen applicants were a whopping 34 percentage points and 54 percentage points more likely to receive a request to interview relative to White and Indian citizen applicants, respectively.7

The IT firm Cognizant was recently found guilty by a jury of intentionally discriminating against two-thousand non-Indian employees on the basis of race and national origin.

This evidence of discrimination combined with a decreasing supply of jobs in tech lends itself to a very clear conclusion: the H-1B program actively harms native employment.

What is the pro-H-1B prior?✅

The entire anti-H-1B prior rests on an erroneous assumption: namely, that the # of jobs in the economy is fixed. This assumption is so deeply fallacious that it has earned a derisive name from economists: the lump of labor fallacy.

Were the lump of labor fallacy true, the introduction of women into the labor force should have caused a permanent mass recession among working-age men. Given that such sustained economic devastation has not taken place, we should be highly skeptical of any attempts to invoke the lump of labor fallacy in defense of one’s economic views.

Beyond this point, there are several reasons to believe that H-1B workers positively impact the employment of natives by increasing demand for labor:

Increased Firm Survival: By increasing the probability that a firm remains profitable, H-1B workers allow the firm to continue employing additional workers, many of whom would be native to the US.

Labor Complementarities: Complementarities occur when the skills of immigrants and natives complement one another. For example, an influx of H-1B software engineers might lead a firm to hire additional US-born managers who serve as mediators between H-1B employees and upper-level management.

Entrepreneurship: From Moderna Co-Founder Noubar Afeyan to Instagram Co-Founder Mike Krieger, several of the most impactful innovators and leaders in the present day had their humble origins as H-1B workers. These individuals undeniably had a net positive impact on native employment by successfully building companies based in the US.

Consumption: Because immigrants are people just like us who consume goods and services, an influx of immigrants results in increased demand for people to provide such goods and services. For example, more immigrants will increase demand for food which will, in turn, lead to increased hiring of grocery store and restaurant staff.

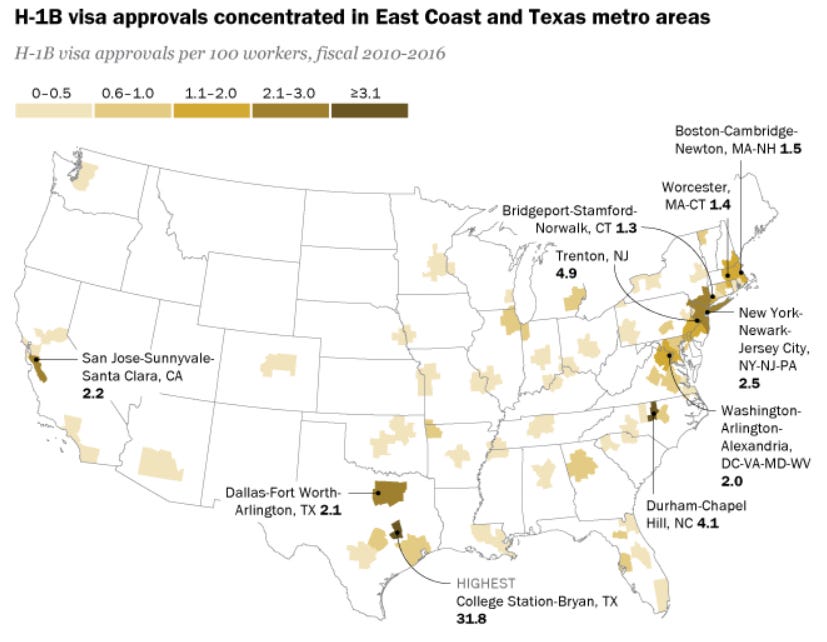

Industrial Clustering: Economist Noah Smith points out that, by bringing workers from abroad to the US, the H-1B program concentrates talent domestically, encouraging companies to invest domestically. This additional investment then has spillover benefits in the form of increased native employment.

What does the causal evidence say?📈

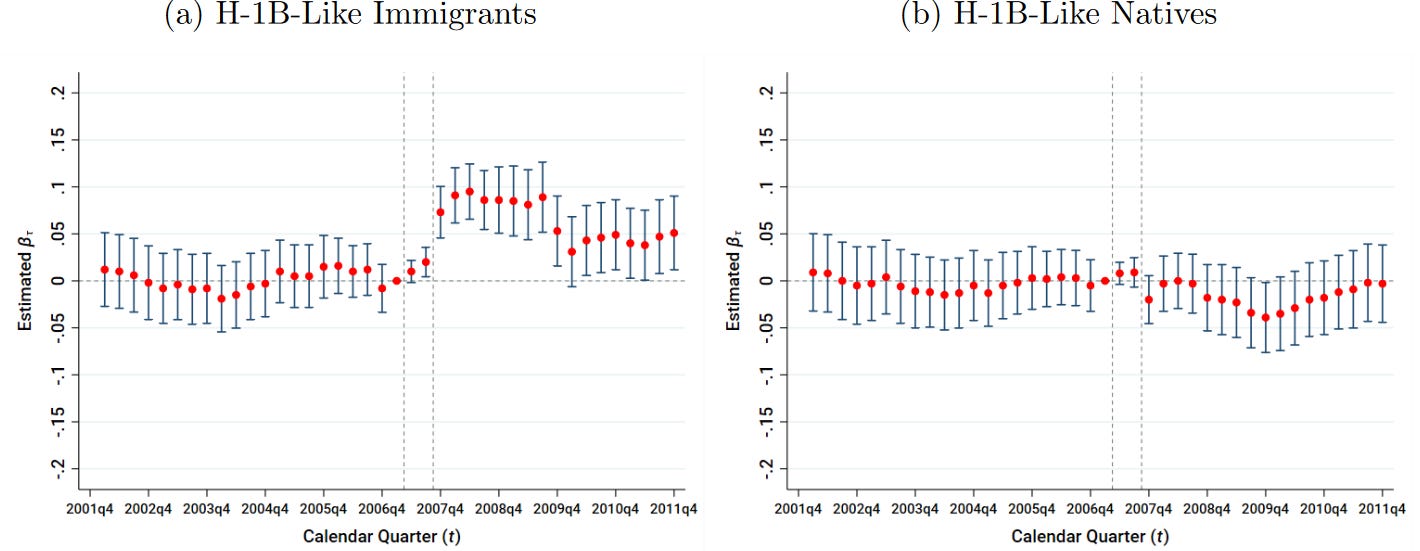

Two studies leverage the FY 2006-2008 lotteries to estimate the causal impact of the H-1B visa program on native employment. In particular, they answer the question: how many native workers does one H-1B worker crowd out? Both studies find that the answer to this question is not significantly different from zero.

Mahajan et al go one step further and analyze the subset of native workers most comparable to H-1B workers: college-educated young workers with less than 3 years of tenure at the company. While they do observe a short-run negative impact on this population of “H-1B like” natives, this impact reassuringly does not persist in the longer-run.

So case closed, right? Not quite. First, Mahajan et al note that, because of the law of large numbers, the impacts they estimate in the subset of large firms are riddled with uncertainty. This uncertainty matters because it leaves a core premise of the H-1B critic’s argument tenable: namely, that large tech firms such as Cognizant displace native workers in favor of foreign workers.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, Mahajan et al note that, at large firms, higher win rates in the H-1B visa lottery did not translate to a significantly higher # of college-educated foreign employees.

This counterintuitive result is likely driven by compensatory behavior: large firms which suffer high losses in the H-1B lottery compensate by poaching H-1B visa holders from other companies and/or seeking skilled foreign labor through alternative visa programs like the TN visa.

This compensatory behavior matters because it would leave the H-1B critic’s key hypothesis completely untested by the lottery study: namely, that additional skilled foreign labor displaces skilled natives. Because large firms ended up hiring a similar # of skilled foreign workers regardless of how many H-1B visas they actually won, Mahajan et al does not actually estimate the causal impact of additional foreign labor on native employment in the subset of large firms.

Thus, the aforementioned lottery studies are unable to shed much light on native displacement in large tech firms. But what about long-run channels that positively impact employment such as increased firm survival and industrial clustering?

Two studies leverage the FY 2008-2009 and FY 2014-2015 lotteries to estimate the causal impact of H-1B workers on start-up growth. Both studies find that start-ups with higher H-1B lottery win rates are more likely to grow whether it be through receiving additional venture capital funding, undergoing an IPO, or being acquired.

Glennon (2023) leverages the FY 2008-2009 lotteries to estimate the causal impact of H-1B lottery losses on the tendency of multi-national corporations (MNCs) to offshore jobs. As a lower bound, she finds that each additional H-1B lottery loss corresponds to a 0.42 increase in the # of jobs at MNC foreign affiliates.8

Thus, the above studies provide strong reason to expect long-run positive employment impacts that would not be captured in short-run lottery studies.9

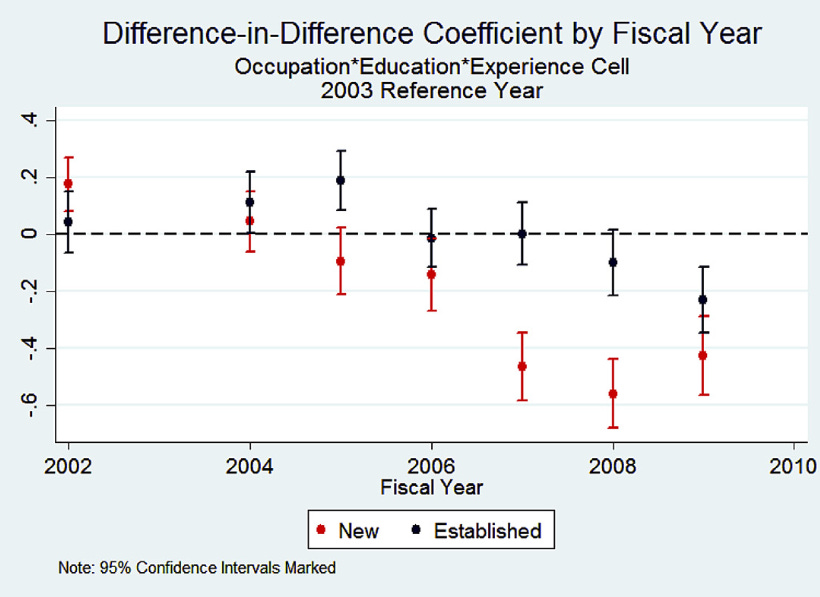

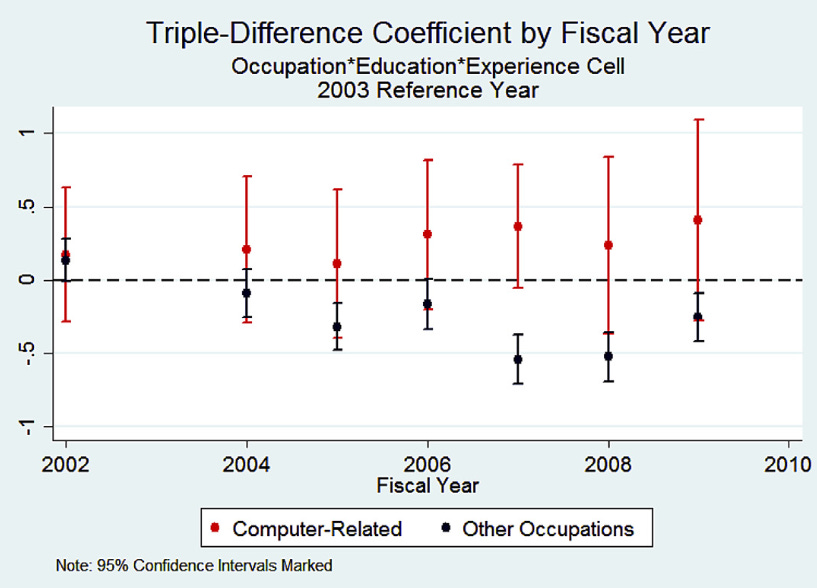

The last causal study relevant to native employment is Mayda et al (2018). This study uses the difference-in-differences method to estimate the causal impact of the 2004 reduction in the H-1B cap from 195k to 65k. Specifically, they examine how the difference in the # of workers employed at for-profits vs non-profits changes as a result of the 2004 cap reduction which only impacted for-profit firms.10

Consistent with the intended effects of the policy, they observe a large decrease in the # of new H-1B visa workers at for-profits relative to non-profits following the cap reduction.

However, they do not observe a corresponding increase in the # of “H-1B like” natives employed at for-profits relative to non-profits:

The results do not suggest any change in relative demand for native workers after 2004. The gap between new and established native employment in for-profit relative to non-profit sectors did not change significantly after 2004.

Thus, the study provides strong evidence that the reduction in the cap did not materially improve native employment.

Critically, however, this result may still be consistent with the H-1B critic’s key hypothesis about native displacement: namely, that large tech firms displace native workers with foreign labor. This conclusion is still tenable because Mayda et al show that the cap did not reduce the # of H-1B workers employed in computer-related occupations.

Because the # of H-1B workers in computer-related occupations did not actually decrease as a result of the 2004 cap reduction, there is no reason for the H-1B critic to expect a corresponding increase in the # of “H-1B like” natives employed in computer-related occupations to take place. In light of this finding, Mayda et al state:

Our data and results cannot ascertain whether it is true that the H-1B program is used by firms to hire Indian-born computer-related workers in order to displace (or outsource) Americans’ jobs.

Thus, economists must be very careful to avoid using this study to magically wave away concerns that the H-1B program displaces native tech workers *cough Noah Smith*.

What can we conclude?🤔

Based on both the prior evidence and causal evidence, I hold that the view that the H-1B visa program does not harm native non-tech employment but may harm native tech employment depending on the broader context (e.g. employer, time horizon).

The H-1B visa program does not harm native non-tech employment.

The strongest piece of evidence to this end is Mayda et al - the cap change study. Even when the size of the H-1B program was slashed by 70% (causing a sustained drop in the # of foreign skilled workers employed in non-tech occupations), there was no corresponding increase in the employment of college-educated native workers. This study provides very strong evidence that foreign workers are likely not displacing natives at non-tech employers.

The H-1B visa program may harm native tech employment depending on the broader context.

I think the impact on native tech employment varies based on time horizon:

In the short-run, we have both descriptive evidence which indicates that the supply of tech jobs has decreased substantially relative to pre-pandemic levels, and causal evidence which indicates that the H-1B program negatively impacts the employment of “H-1B like” natives.

In the long-run, however, the causal evidence is consistent with a neutral-to-positive impact on native tech employment. There is no long-run negative impact on employment of “H-1B like” natives at small firms, and increased hiring of H-1B workers reduces offshoring and increases start-up growth.

I also think the impact on native employment varies by employer:

The audit study conducted by Lambert and Akinlade weighs heavily on my mind in this regard. There is simply no reason to expect such a large differential response to resumes sent by citizens vs student visa holders unless some subset of tech employers are actively discriminating against native workers.

That being said, I strongly suspect that there are also employers who behave in the opposite regard: namely, they automatically reject student visa holders because they do not wish to undergo the burdensome H-1B visa sponsorship process. Ultimately, a large-scale audit study could explore this heterogeneity in greater detail.

Native Wages

What is the pro-H-1B prior?✅

Employers are legally mandated to pay the maximum of the prevailing wage and actual wage for the position in question. Consistent with this mandate, we can clearly observe that the average wage listed on the LCAs submitted by top employers is at least as high as the prevailing wage (Bier 2020).

Furthermore, multiple analyses of salary data indicate that wages of workers on visas are at least as high as those of similarly-employed native workers and, importantly, this result is equally true when analyzing the IT industry which is often accused of replacing natives with “cheap labor”. For example:

Mithas and Lucas (2010) find that temporary work visa holders in the IT industry earn at least as much in annual compensation as US citizens, controlling for years of IT experience, hours of work per week, educational credentials, job title, employer size, and state.11

Bagheri (2023) finds that college graduates on a temporary work visa in the IT industry earn 50% more in hourly wages relative to those not on such a visa, controlling for age, race, educational credentials, field of education, employer sector/size/region, whether the immigrant was from an English-speaking country, and age at arrival in the US.12

Thus, the empirical evidence directly contradicts the narrative that H-1B workers depress native wages.

But what about claims that H-1B workers are paid below the median wage corresponding to their occupation? Such claims are often true but ultimately confused. Because H-1B workers are disproportionately entry-level, we should not expect that they make the median wage corresponding to their occupation. Requiring H-1B workers to be compensated at this level would be tantamount to claiming that a fresh-out-of-college software developer ought to be paid comparably to a developer with multiple years of on-the-job experience. No one seriously believes this, and neither should you.

It should also be noted that the anti-H-1B case rests on a fundamentally paradoxical argument.

On the one hand, the case presumes that H-1B workers are easily able to displace native workers from their jobs (i.e. companies really want to hire them).

But on the other hand, the case also argues that H-1B workers are indentured servants who cannot effectively negotiate for higher wages because they remain anchored to their original employer (i.e. companies don’t really want to hire them).

So which is it? Are H-1B workers so highly desired by companies that they displace natives? Or are they desired so little that they remain unable to leave the employers who initially sponsored their visa? Both cannot be true simultaneously.

Lastly, we have strong reason to believe that the H-1B program increases the wages earned by natives working in blue-collar professions. Why? For the simple reason that H-1B workers demand services from blue collar workers without competing against them in the labor market.

Thus, the H-1B critic’s position ought to be viewed not as a defense of high native wages but rather as a defense of high wage inequality between natives in white-collar professions and natives in blue-collar professions. When viewed through this lens, it is not at all obvious whether the H-1B critic’s position satisfies his own stated objective of placing Americans first.

What is the anti-H-1B prior?❌

Basic market theory compels us to believe that H-1B workers decrease native wages. To start, note that H-1B workers must be sponsored by an employer to remain in the country. Because these workers’ visas are attached to their employer, they are less able to leverage the threat of leaving to a new company in exchange for higher compensation, and consequently, are more likely to suffer in silence with a below-market wage.

This hypothesis is well-supported by the existing body of economic literature. For example, workers who are randomly assigned to a non-compete (which limits their ability to work for a competitor) have ~5% lower earnings relative to workers randomly assigned to a non-compete-free contract (Cowgill, Freiberg, and Starr 2024).13

While one may counter that H-1B visas are not as restrictive as non-competes (in the sense that an H-1B worker is still able to transfer their visa to a new company), it is undeniably true that H-1B visa workers face greater friction in switching jobs relative to the average citizen due to the sheer number of regulations involved.

This point becomes most obvious when one looks at the permanent residence application process. You see, if an H-1B visa holder switches employers during this process, they will lose their spot in the green card line and have to start over unless they meet the following criteria (USCIS 2024b):

They have an approved I-140 petition (i.e. a permanent residence petition).

They’ve submitted Form I-485 to apply for permanent residence, and this application has been pending with USCIS for at least 180 days since the day it was received.

The new job is in the same or similar occupation as the previous job.

Consistent with such restrictions, we see that H-1B visa holders experience a much smaller wage increase upon immigrating to the US relative to those who immigrate with a green-card (which does not anchor one’s residence to a given employer). Though this wage difference just misses the threshold to achieve statistical significance, it is economically significant on the order of a ~$5/hour wage decrease.

But what about the requirement to pay workers at or above the prevailing wage? There are two points worth noting:

First, just because an employer claims that they are paying the higher of the prevailing wage and actual wage on the LCA does not mean they actually do in practice. For example:

A 2008 audit conducted by USCIS concluded that ~6% of H-1B visa applicants are paid below the prevailing wage.

A 2024 study analyzing Deloitte payroll data found that H-1B visa applicants were offered salaries ~10% lower relative to salaries earned by employees in the same entry-level position at the same office.

Second, the prevailing wage calculation is itself deeply flawed. For example, UC Davis Computer Science Professor Norm Matloff points out that it does not take into account the wage impact of possessing specific job-relevant skills (e.g. Android vs iOS vs web development), and correspondingly, cannot meaningfully distinguish between employees with different skill sets.

Thus, the existing prevailing wage statutes contain serious loopholes that companies can exploit to underpay workers.

But what about the studies which claim to show evidence that foreign workers have a salary premium relative to natives? Put simply, these studies do not control for several confounding variables including, but not limited to, residential area (which proxies cost-of-living) and specific job-relevant skills (e.g. Android vs iOS vs web development). Given that immigrants are more likely to live in urban areas relative to citizens, any study which does not control for residence is effectively meaningless.

Lastly, the so-called paradox presented by the pro-H-1B case is not a paradox at all but rather is entirely consistent with a relatively monopsonistic labor market for H-1B workers. For context, labor market monopsony takes place when there is one buyer and many sellers in a labor market (think of a factory town). Because those selling their labor (the townsfolk) are entirely dependent on a singular buyer (the factory) for employment, that buyer has the power to depress wages to below-market levels.

How does this relate to the H-1B visa? Well, as Kim and Pei (2023) explain, H-1B workers are effectively limited to working for those firms with sufficient in-house legal expertise to navigate the visa application process. Such firms can then leverage this market power to pay workers below-market wages, setting the conditions for a relatively monopsonistic labor market.

Thus, the so-called “paradox” is resolved:

Companies with sufficient access to legal expertise are happy to hire H-1B workers because they know such workers will accept below-market wages in the US (since it’d still be higher than the wage they’d earn abroad).

The high regulatory barriers to entering the H-1B labor market as an employer create a relatively monopsonistic labor market, enabling employers to keep wages at below-market levels.

What does the causal evidence say?📈

One study leverages the FY 2008 lottery to estimate the causal impact of the H-1B visa program on native wages. In the aggregate, the impact on native wages is a wash: some native workers benefit while others do not.

That being said, it’s worth re-emphasizing that this study did not find that a higher lottery win rate translated into a greater # of skilled foreign workers at large firms to begin with. Thus, their analysis of wage impacts is only relevant to their sample of small firms (defined as ≤ 100 employees).

Regarding cap change studies, there are unfortunately none which estimate the impact of H-1B workers on the wages of native workers specifically.

What can we conclude?🤔

Based on the prior evidence and causal evidence, I hold an agnostic view on the wage impact of the H-1B visa program. My rationale is as follows:

H-1B visa holders are likely underpaid relative to their native counterparts.

I find the anti-H-1B prior here to be much more convincing than the pro-H-1B prior. Yes, prevailing wage laws exist and yes, some studies don’t find evidence of under-payment, but such laws have known deficiencies, and such studies are obviously confounded. Conversely, the job friction theory put forth by the H-1B critic is both intuitive and supported by higher-quality data (e.g. the audit study and the Deloitte payroll study).

But this under-payment does not necessarily translate into a negative impact on native wages.

On one hand, it seems natural to assume that the under-payment of H-1B workers should negatively impact native wages because such workers could use their lower wage as a bargaining chip, thereby forcing native workers to accept lower wages if they wish to be employed (i.e. “I’m willing to do the same amount of work for less!”).

But on the other hand, this mechanism is not supported by what little causal evidence exists. Even the Deloitte payroll study (which found substantial evidence of under-payment) did not find evidence that such under-payment negatively impacted native wages. On top of that, this mechanism says nothing about the wages of native blue-collar workers who are expected to see a wage increase as a result of increased demand from H-1B workers. Ultimately, given the dearth of causal evidence on this subject, I think holding an agnostic view is most appropriate.

Productivity

What is the anti-H-1B prior?❌

Loyalka et al (2019) assessed the computer science (CS) skills of seniors in bachelor’s degree programs in the US, China, Russia, and India. Importantly, they go to great lengths to ensure that the samples are nationally representative, carefully matched to one another, and include schools whose curricula actually cover the material assessed on the test. Contrary to what H-1B proponents might have you think, students in the US have greater CS skills than international students and it isn’t even remotely close!

Importantly, this result is neither explained by differences in gender composition nor is it explained by the high-achievement of international students attending US institutions. Thus, we have strong reason to expect that native US graduates are genuinely more skilled than their international counterparts.

What is truly remarkable about these results, though, is that even US graduates of mid-tier institutions outperform international graduates at elite institutions. Thus, claims that elite talent from abroad will contribute to domestic productivity are highly exaggerated.

Lastly, to the extent that international workers do demonstrate high productive potential, they are more than welcome to enter the country using the O-1 visa which, importantly, does not have a cap because the US has a genuine interest in relocating proven talent here.

What is the pro-H-1B prior?✅

One reason we should expect skilled immigrants to impact productivity is because location itself has a strong causal impact on high-achieving individuals’ output. For example:

Agarwal and Gaule (2020) document that International Math Olympiad (IMO) participants from high-income countries are a whopping 16 percentage points more likely to obtain a PhD in mathematics even when they achieve the exact same score as IMO participants in low-income countries14

Prato (2022) documents that European inventors immediately increase their patenting activity upon immigrating to the United States.

Thus, by bringing skilled immigrants to the US where their talents will be put to effective use, we have every reason to expect that the H-1B program enhances productivity.

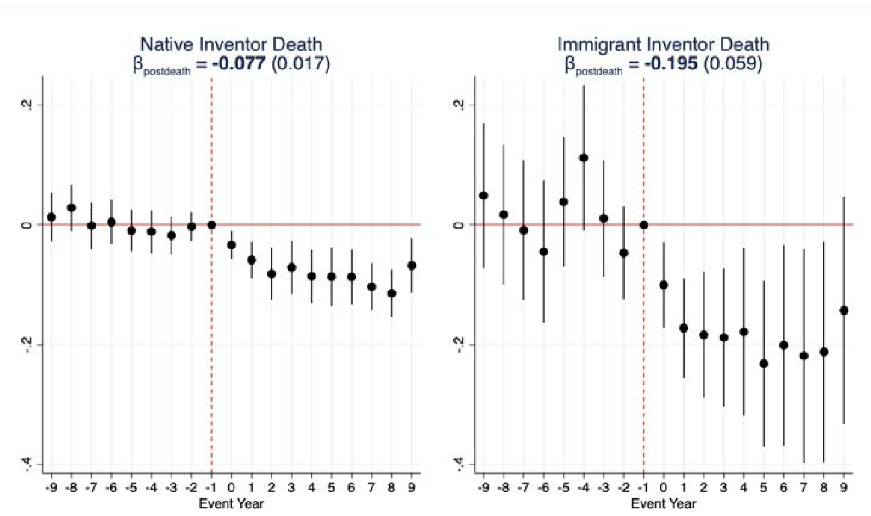

Beyond this point, it’s worth noting that immigrants drive 25% of innovation in the US despite only making up 16% of the population.15 This impact has clear implications. For example, when native-born inventors experience the premature death of an immigrant co-inventor, their subsequent innovative output is substantially reduced, and this decrease in output is qualitatively larger than the decrease caused by the premature death of a native-born co-inventor (though it’s admittedly difficult to say whether it’s significantly larger).

While it is true that US graduates have measurably stronger computer science (CS) skills than their international counterparts, this result might ironically support skilled immigration. Why? For the simple reason that the high scores in the US are likely driven by the children of skilled immigrants.

Technically speaking, it is not possible to directly test this hypothesis because Loyalka et al do not disaggregate their results based on second-generation immigration status. But given that Asian-American college students are disproportionately high-achievers, children of immigrants, and computer science bachelor’s degree recipients, one should have a very strong prior that the US advantage in computer science skills is driven by children of skilled immigrants. Thus, dramatically reducing the scale of the H-1B visa program will likely only decrease the average competency of US CS graduates in the long-run.

Lastly, there is an obvious philosophical problem with relying solely on the O-1 visa to acquire skilled immigrants: namely, it assumes that the government is capable of identifying ex ante which skilled individuals will belong to the next generation of innovators and leaders and which ones will not. This task is much easier said than done. For example:

Would the government have been able to predict that Satya Nadella would lead Microsoft at the time he only possessed a Master’s in Computer Science from the University of Wisconsin?

Would the government have been able to predict that Sundar Pichai would lead Google at the time he only possessed a Bachelor’s Degree in Metallurgical Engineering from IIT Kharagpur?

Would the government have been able to predict that Yann LeCun would be an internationally-acclaimed leader in machine learning research at the time he only possessed an Engineering Degree from ESIEE Paris?

… you get the point.

Because the government simply cannot identify all revolutionary needles in a worldwide haystack, we should ideally leave this task to the market, or at the very least, the H-1B program which can cast a wider net to identify the leaders and innovators of the future.

What does the causal evidence say?📈

Productivity is a tricky concept to measure, but there are generally 4 ways it is proxied in the H-1B causal literature:

Wages: Workers that are more productive receive higher wages.

Innovation: Workers that are more productive are more likely to patent new technologies.

Accuracy: Workers that are more productive are less prone to making mistakes.

Ability: Workers that are more productive have higher human capital.

Let’s tackle each of these measures in succession.

Wages

Clemens (2013) documents that the wages of Indian developers at an unnamed software company shot up by a whopping $58k/year as soon as they won a visa in the H-1B lottery. This result can only make sense if the company truly believed that these workers were more productive in the US.

While an H-1B critic is welcome to argue that this pay raise only is only profitable because it allows the company to fire a higher-paid native worker, the basic point holds true: no rational company would offer a worker a massive pay raise upon immigrating to another country unless being in that country genuinely increased their productivity. Thus, the lottery evidence provides strong reason to believe that the H-1B program materially improves the productivity of foreign workers.

Innovation

Two studies leverage the FY 2006-2008 lotteries to estimate the causal impact of the H-1B visa program on the # of patent applications filed by a company and the # of patents granted to the company.16 Both studies find that H-1B workers have basically zero positive impact on patenting outcomes.

Wu bluntly summarizes this pattern of results like so:

The median H-1B immigrant is a young Indian software engineer or information technology support specialist and not a patent-generating researcher or scientist, and many of these immigrants are not even employed by their hosting firm.

So case closed, right? Not so fast. Both studies are limited in different ways:

Doran et al only study the subset of lottery applicants who were the last to submit their petitions in the corresponding fiscal year. This means their results may not generalize to those applicants whose companies were eager to sponsor early on due to their high expected innovative output.

Wu only studies H-1B visa applicants in the Regular Cap lottery. Because innovation would presumably be driven by applicants with advanced degrees, the null results he estimates should not be particularly surprising.

Consequently, when one estimates the causal impact of H-1B workers in start-ups, the impact on innovation becomes much starker:

Thus, while the average H-1B worker may not impact innovation, H-1B workers at start-ups most certainly do.

Accuracy

Two studies estimate the causal impact of the H-1B program on the probability that a company issues a financial restatement - an acknowledgement that previous financial reporting issued by the company contains an error:

Using the FY 2008-2009 and FY 2014-2020 lotteries, Aobdia, Carnes, and Munch (2024) find that startups which win all of their visa accountants are less likely to issue financial restatements and more likely to produce accurate forecasts.

Using the 2004 cap change which reduced the H-1B cap from 195k to 65k, Frost et al (2024) find that H-1B reliant firms experienced a ~6 percentage point increase in the probability of issuing a financial restatement as a result of the cap change.

Thus, the H-1B program measurably improves the quality of financial reporting issued by firms.

Ability

Kato and Sparber (2013) uses the difference-in-differences method to estimate the causal impact of the 2004 cap reduction on the skill of prospective H-1B workers as proxied by the SAT scores of international students applying to US universities. In the aggregate, they find that the 2004 cap change decreased the average SAT score of international applicants by 20 points on a 1600 point scale. While this impact may initially seem marginal, the real worrisome result is that the cap change hit applicants at the tails of the SAT score distribution the hardest.

In other words, while the cap change desirably reduced the # of low-quality applicants (who likely realized that their chances of being sponsored by an employer would decrease), it also undesirably decreased the # of high-quality applicants (who likely did not want to bother with an uncertain immigration status here in the US when they were highly desired elsewhere). Because it is that high-end of the ability distribution that is most likely to generate high-impact, this study provides a cautionary tale about the dangers of arbitrarily slashing the size of the H-1B program.

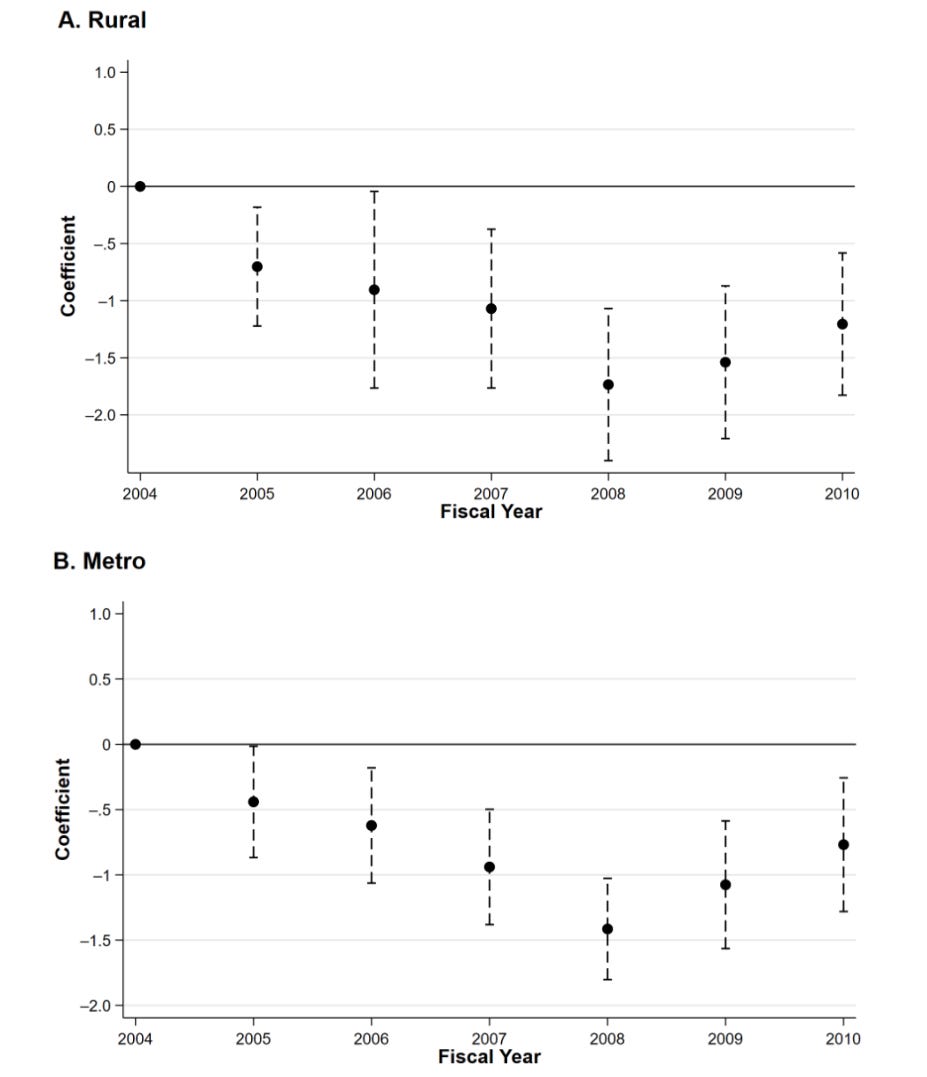

Castillo (2024) double-click into this result by estimating the impact of the 2004 cap change on a profession known to require high ability: physicians. He ultimately finds that, in both rural and urban areas, for-profit hospitals hired ~65% fewer foreign-born attending physicians as a result of the cap change.

Although the study does not directly estimate the impact of this decrease on health outcomes, multiple studies indicate that foreign doctors causally improve health outcomes in their own countries, providing suggestive evidence that they would do the same in impoverished communities here in the US as well.17 Thus, both studies provide us with strong reason to believe that the 2004 cap change undermined the welfare of the native-born population by decreasing the supply of high-ability workers.

What can we conclude?🤔

Based on the prior evidence and causal evidence, I hold the view that the H-1B program positively impacts productivity.

The H-1B program positively impacts productivity.

The causal evidence clearly lends support to this conclusion:

H-1B workers are much more productive here in the US than abroad.

H-1B workers at start-ups actively contribute to innovation via patenting.

H-1B accountants increase the quality of financial reporting.

The H-1B program provides an incentive for high-ability students from abroad to study and work in the US.

Fiscal Impact

Thus far, I have focused on economic impacts of H-1B workers: do such workers displace natives? do they increase productivity? etc. But I think it’s also worth highlighting the fiscal impact of H-1B workers. In other words, do H-1B workers pay more in taxes to the government than what they would receive from the government during their lifetime?

Manhattan Institute Fellow Daniel DiMartino has crunched the numbers, and the answer to this question is a resounding yes.

DiMartino describes multiple reasons why younger college-educated immigrants have a stronger fiscal impact than native-born citizens:

Benefit spending drives most of the difference in fiscal impact between these groups … The reason this immigrant group receives fewer government benefits is that they come to the U.S., on average, at the age of 29, so they never receive any public education or CHIP, and by having higher earnings, they are much less likely to be on Medicaid or receive SNAP and other welfare benefits. They also consume fewer public goods than natives because they lived for about a third of their life outside the United States.

While one may challenge certain methodological assumptions built into the estimates, the general finding that H-1B workers have a net positive fiscal impact is intuitive and could only be overturned using unrealistic modeling choices in my opinion.

Policy Solutions

While it’s easy to get lost in the sauce of studies analyzing the impact of the H-1B program, it’s important to keep in mind that data analysis is not an end in and of itself. Rather, the point of data analysis to ultimately make data-driven decisions. So let’s do exactly that! Based on the data-driven conclusions we reached about the H-1B visa program, what policies should the federal government implement to maximize its value to the American people moving forward?

Salary-Ranked Selection

One policy idea that has gained broad political appeal is replacing the lottery-based selection system with a salary-ranked selection system. This idea has multiple advantages:

It captures the highest-quality talent. UC Davis Computer Science Professor Norman Matloff points out that salary-ranked selection effectively achieves the goal of attracting the “best and brightest talent” to the US. Because companies are only willing to pay top dollar for top talent, a salary-ranked system will screen out low-wage mediocre applicants by construction. In particular, the Institute For Progress estimates that the median H-1B worker would earn a salary of ~$130k under such a proposal.

It updates in real-time to reflect high-demand skills. The salary offered to a worker captures a number of traits which are not adequately incorporated into prevailing wage calculations. For example, whereas the prevailing wage fails to distinguish between software developers proficient in different programming languages, a salary offer certainly will. This advantage is particularly important because the relative value of different skills shifts rapidly in the tech industry, and salaries update in real time to reflect this change in value.

It’s less gameable. IT giants have allegedly attempted to game the H-1B visa program by flooding the lottery with many more applicants than the company needed to meet headcount goals. This behavior would be very difficult to pull off in a salary-ranked system because the IT giants would be priced out of the system by competitors willing to pay a higher wage.

There are, however, 4 key challenges faced by a salary-ranked system:

It favors high cost-of-living areas, high-tenure employees, and higher-paying industries. These consequences are undesirable because:

Contrary to popular belief, a great deal of innovation does in fact happen in places other than Silicon Valley. For example, if you ditch the warm weather and head out to Minnesota, you’ll find a lot of cool innovation in the medical device space!

Ideally, we want to attract immigrants when they’re relatively young. Attracting immigrants at an earlier age will both increase their fiscal impact (because they’ll spend more years in the workforce) and provide them with an opportunity to take entrepreneurial risks.

Not all high-skilled professions pay particularly well. For example, medical residents on H-1B visas make less than $65k/year. These professionals would effectively be priced out of the H-1B market in a system which purely rewards salary.

It would be administratively costly. A key advantage of the lottery-based system is that USCIS is only obligated to adjudicate those petitions that were actually selected in the lottery. Switching to a salary-ranked system, however, would require USCIS to adjudicate the salaries listed on all petitions and then rank submissions accordingly … only to then dump ~70% of petitions in the trash! This process would be administratively inefficient.18

It’s anti-competitive. By only offering H-1B visas to those employers willing to pay top dollar, a salary-ranked system necessarily favors The Big Guys™ who can afford to shell out such money. This consequence is undesirable because, if anything, the causal evidence most clearly vindicates start-ups: H-1B workers at start-ups increase innovation and investment with little evidence of native displacement. Given this reality, why would we wish to penalize them?19

It’s still gameable. In theory, one could artificially boost their salary ranking by either taking out a loan (on the expectation that their wage in the US will be higher than the wage earned in their country-of-origin) or leveraging connections to wealthy family members. The salary-ranked system would then undermine the very meritorious qualities it was intended to reward.

Thus, while I believe a salary-ranked system absolutely represents a step in the right direction, lawmakers should consider these nuances before adopting it.

Salary-Based Job Mobility

Critics of the H-1B program are right to point out that H-1B workers are less able to switch jobs, and as a result, less likely to be paid market wages. Importantly however, the solution to this challenge lies not in imposing additional regulations - which would only entrench the very monopsonistic conditions which created this problem in the first place. Rather, the solution must lie in replacing the existing system with one which is less burdensome to both H-1B workers and their employers.

The Economic Innovation Group has proposed exactly such a policy: namely, all an H-1B visa holder must do to switch employers is demonstrate that their prospective salary will be at least as high as the salary used to enter the country. This policy has two clear advantages relative to the existing system:

It removes arbitrary restrictions on job mobility. Current policy requires H-1B workers to be employed in “specialty occupations” - a designation which relies on the government accurately updating its inventory of skilled occupations from year to year. Rather than relying on potentially slow-to-update government classifications, the policy proposal allows H-1B workers to move wherever their skills are in high demand (as reflected by their salary).

It seems administratively efficient. I say “seems” because I don’t want to talk out of my ass as someone who hasn’t done much civil service in my life. But my reasoning is as follows. Current policy requires the Department of Labor to certify that the H-1B worker will be paid the prevailing wage associated with the job in question - in other words, do a bunch of number-crunching using a woefully incomplete dataset to figure out whether the worker is underpaid. Conversely, the new policy simply requires comparing the salary offer given by the new company to that given by the original sponsoring company - no real number crunching needed.

There are, however, 2 key challenges faced by a salary-based mobility system:

Inflation. Under the proposed policy, it would be legally acceptable to offer a prospective H-1B worker a salary which is only nominally higher than the salary they used to enter the country. This behavior would then undermine the policy’s stated goal of permitting job flexibility insofar as it is economically efficient.

It’s gameable. Under the proposed policy, companies may simply fabricate salary offers all the while paying H-1B workers well below their stated compensation.20

Thus, while I believe a salary-based job mobility system absolutely represents a step in the right direction, lawmakers should consider these nuances before adopting it.

Abolishing H-1B

The most controversial policy I’ve seen proposed to deal with the weaknesses of the H-1B program is to simply abolish it and limit skilled immigration to only the most selective channels (e.g. O-1 visa, EB-1 green card).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, I do not support such a proposal for multiple reasons:

First, the causal evidence clearly and consistently demonstrates that start-ups use the program to increase both innovation and access to investment. Abolishing the program would rid these businesses of the ability to grow in a manner that will likely benefit natives in the long-run.

Second, there is no causal evidence to suggest that H-1B workers displace natives in non-tech industries. Abolishing H-1B would thus decrease the supply of physicians with little benefit to natives.

Third, abolishing H-1B would throw the baby out with the bathwater. While low-ability immigrants would be deterred from applying, so too would high-ability immigrants because they wouldn’t bother dealing with a cumbersome immigration process in the US when they’re highly desired elsewhere.

Fourth, there are obvious macroeconomic consequences to abolishing the H-1B visa program. We would severely restrict ourselves from bringing in exactly the type of immigrants with net positive fiscal impact, placing a greater fiscal burden on the native working-age population.

Conclusion

If you’ve made it this far into the essay, I commend you! Learning about each and every one of the studies presented in this essay is no easy task. We can end our journey by recapping the conclusions supported by the causal literature on the H-1B visa:

The H-1B visa program does not have a negative impact on native non-tech employment. Slashing the size of the H-1B visa program by ~70% led to a permanent drop in the # of H-1B workers employed in non-tech occupations, yet this decrease was not met with a corresponding increase in the employment of native workers. This lack of an impact on native workers provides strong reason to believe that H-1B workers were not being used to displace native workers in non-tech occupations to begin with.

The H-1B visa program may have a negative impact on native tech employment. There is good reason to believe that the H-1B visa program displaces native tech workers in the short-run: tech jobs are in short supply at the moment, and lottery studies highlight evidence of a negative short-run impact on native employment. At the same time, however, there are multiple mechanisms which may very well overturn this impact in the long-run (e.g. start-up growth and reduced offshoring).

The H-1B visa program has an unclear impact on native wages. While it is highly plausible that H-1B workers are paid less relative to their native-born counterparts, the available causal evidence does not indicate that this underpayment impacts said native workers, and economic theory suggests that the wages of blue-collar native workers should actually benefit from the presence of H-1B workers. Given the dearth of causal evidence on this subject, I hold a relatively agnostic view.

The H-1B visa program increases the productivity of US businesses. Whether one measures productivity using patenting, on-the-job-accuracy, wages, or ability, the existing body of research highlights multiple ways in which H-1B workers increase the productivity of US businesses.

Given these conclusions, I believe it would incredibly unwise to abolish the H-1B visa program. Instead, policymakers should deal with problems inherent to the existing system by switching to one which emphasizes salary over cumbersome prevailing wage requirements. While a salary-based system will inevitably introduce its own set of challenges, I believe that these challenges are certainly worth tackling to ensure that both the American people and aspiring Americans alike are able to jointly contribute to and rejoice in our nation’s prosperity.

Works Cited

Agarwal, R., & Gaule, P. (2020). Invisible Geniuses: Could the Knowledge Frontier Advance Faster? American Economic Review: Insights, 2(4), 409–424. https://doi.org/10.1257/aeri.20190457

Aldighieri, P, Bourne, R., & Miron J. (2022). Is There Monopsony Power in U.S. Labor Markets? Cato Institute. https://www.cato.org/regulation/summer-2022/there-monopsony-power-us-labor-markets

American Immigration Council (2024). The H-1B Visa Program and Its Impact on the U.S. Economy. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/h1b-visa-program-fact-sheet

Amuedo-Dorantes, C., & Furtado, D. (2019). Settling for Academia?: H-1B Visas and the Career Choices of International Students in the United States. Journal of Human Resources, 54(2), 401–429. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.54.2.0816.8167R1

Aobdia, D., Carnes, R., & Munch, K. (2024). The Role of High-Skilled Foreign Accounting Labor in Shaping U.S. Startup Outcomes. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4686400

Bagheri, O. (2023). Are College Graduate Immigrants on Work Visa Cheaper Than Natives? Journal of Labor Research, 44(3–4), 228–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-023-09349-2

Berkeley International Office (2024). H-1B Frequently Asked Questions. UC Berkeley. https://internationaloffice.berkeley.edu/h-1b_faqs

Bernstein, S., Diamond, R., Jiranaphawiboon, A., McQuade, T., & Pousada, B. (2022). The Contribution of High-Skilled Immigrants to Innovation in the United States. NBER. https://www.nber.org/papers/w30797

Bier, D. J. (2020). 100% of H‑1B Employers Offer Average Market Wages—78% Offer More. Cato Institute. https://www.cato.org/blog/100-h-1b-employers-offer-average-market-wages-78-offer-more

Bourveau, T., Stice, D., Stice, H., & White, R. (2024). H-1B Visas and Wages in Accounting: Evidence from Big 4 Payroll and the Ethics of H-1B Visas. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-024-05823-8

Castillo, M. (2024). US Healthcare Shortages, H-1B Visa Quotas, and Foreign-Born Physicians. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4966745

Chen, J., Hshieh, S., & Zhang, F. (2021). The role of high-skilled foreign labor in startup performance: Evidence from two natural experiments. Journal of Financial Economics, 142(1), 430–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2021.05.042

Clemens, M. A. (2013). Why Do Programmers Earn More in Houston than Hyderabad? Evidence from Randomized Processing of US Visas. American Economic Review, 103(3), 198–202. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.3.198

Costa, D., & H-1B visas and prevailing wage levels. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/h-1b-visas-and-prevailing-wage-levels/

Cowgill, B., Freiberg, B., & Starr, E. (2024). Clause and Effect: Theory and Field Experimental Evidence on Noncompete Clauses. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5012370

Department of Homeland Security (2019). Registration Requirement for Petitioners Seeking To File H-1B Petitions on Behalf of Cap-Subject Aliens. Federal Register. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/01/31/2019-00302/registration-requirement-for-petitioners-seeking-to-file-h-1b-petitions-on-behalf-of-cap-subject

Department of Homeland Security (2024). U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Fee Schedule and Changes to Certain Other Immigration Benefit Request Requirements. Federal Register. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/01/31/2024-01427/us-citizenship-and-immigration-services-fee-schedule-and-changes-to-certain-other-immigration

Department of Labor (2008a). Fact Sheet #62G: Must an H-1B worker be paid a guaranteed wage?. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/fact-sheets/62g-h1b-required-wage

Department of Labor (2008b). Fact Sheet #62Q: What are “exempt” H-1B nonimmigrants?. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/fact-sheets/62q-h1b-exempt-workers

Department of Labor (2020). H-1B, H-1B1 and E-3 Specialty (Professional) Workers. https://foreignlaborcert.doleta.gov/h-1bdd.cfm

DiMartino, D. (2024). The Lifetime Fiscal Impact of Immigrants. Manhattan Institute. https://manhattan.institute/article/the-lifetime-fiscal-impact-of-immigrants

Dimmock, S. G., Huang, J., & Weisbenner, S. J. (2022). Give Me Your Tired, Your Poor, Your High-Skilled Labor: H-1B Lottery Outcomes and Entrepreneurial Success. Management Science, 68(9), 6950–6970. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2021.4152

Doran, K., Gelber, A., & Isen, A. (2022). The Effects of High-Skilled Immigration Policy on Firms: Evidence from Visa Lotteries. Journal of Political Economy, 130(10), 2501–2533. https://doi.org/10.1086/720467

Fan, E., & Jones, C. (2024). Insiders Tell How IT Giant Favored Indian H-1B Workers Over US Employees. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2024-cognizant-h1b-visas-discriminates-us-workers/

Fortt, J. (2017).Microsoft’s CEO Satya Nadella broke unspoken rules on his rise to CEO. NBC News. https://www.cnbc.com/2017/10/02/microsoft-ceo-satya-nadella-broke-unspoken-rules-on-rise-to-ceo.html

Frost, T., Jing, J., Shang, L., & Su, L. (Nancy). (2024). Foreign labor and audit quality: Evidence from newly hired H‐1B visa holders. Contemporary Accounting Research, 41(2), 842–871. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12927

Glennon, B. (2024). How Do Restrictions on High-Skilled Immigration Affect Offshoring? Evidence from the H-1B Program. Management Science, 70(2), 907–930. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2023.4715

Guarin, A., Posso, C., Saravia, E., & Tamayo, J. The Luck of the Draw: The Causal Effect of Physicians on Birth Outcomes. https://www.hbs.edu/ris/Publication%20Files/22-015_741f745f-dc3d-4ae0-814e-01d4903ce53d.pdf

Fan, E., Mider, Z., Lu, D., & Patino, M. (2024). How Thousands of Middlemen Are Gaming the H-1B Program. Bloomberg News. https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2024-staffing-firms-game-h1b-visa-lottery-system/

Hassan, M. (2018). Visa Approved. Stock Vault. https://www.stockvault.net/photo/254259/visa-approved

Indeed (2025). Software Development Job Postings on Indeed in the United States. FRED. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/IHLIDXUSTPSOFTDEVE

Ito, A. (2024). Tech jobs are mired in a recession. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/white-collar-recession-hiring-slump-jobs-tech-industry-applications-rejection-2024-11

Kato, T., & Sparber, C. (2013). Quotas and Quality: The Effect of H-1B Visa Restrictions on the Pool of Prospective Undergraduate Students from Abroad. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(1), 109-126. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00245

Kim, E. (2015). Instagram almost lost one of its cofounders because he couldn't get a work visa. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/instagram-cofounder-mike-krieger-had-an-h1b-visa-problem-2015-4

Kim, E. (2024). Innovation Spillovers from High-skilled Labor Shock. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4558272

Kim, S., & Pei, A. (2023). Monopsony in the High-Skilled Migrant Labor Market: Evidence from the H-1B Visa Program. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4010152

Lambert, J. R., & Akinlade, E. Y. (2019). Immigrant stereotypes and differential screening. Personnel Review, 49(4), 921–938. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-06-2018-0229

Li, A. (2024). Scrambling for Talent: U.S. Startups’ Reactive Strategy to Cope with Visa Restrictions. Academy of Management. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMPROC.2024.351bp

Mahajan, P., Morales, N., Shih, K., Chen, M., & Brinatti, A. (2024). The Impact of Immigration on Firms and Workers: Insights from the H-1B Lottery. https://nicolasmoralesg.github.io/papers/H1B_lotteries_Census.pdf

Matloff, N. (2014). Ten-Minute Summary of the H-1B Work Visa. https://heather.cs.ucdavis.edu/h1b10min.html

Matloff, N. (2025). How the H-1B System Undercuts American Workers. Compact Magazine. https://www.compactmag.com/article/no-there-arent-good-h-1b-visas/

Mayda, A. M., Ortega, F., Peri, G., Shih, K., & Sparber, C. (2018). The effect of the H-1B quota on the employment and selection of foreign-born labor. European Economic Review, 108, 105–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2018.06.010

Mithas, S., & Lucas, H. C. (2010). Are Foreign IT Workers Cheaper? U.S. Visa Policies and Compensation of Information Technology Professionals. Management Science, 56(5), 745–765. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1100.1149

Mukhopadhyay, S., & Oxborrow, D. (2012). The Value of an Employment-Based Green Card. Demography, 49(1), 219–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-011-0079-3

National Center for Education Statistics (2023). Bachelor's degrees conferred by postsecondary institutions, by race/ethnicity and field of study. Digest of Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d23/tables/dt23_322.30.asp

National Center for Education Statistics (2024). Digest of Education Statistics. Number, percentage distribution, and SAT mean scores of high school seniors taking the SAT, by sex, race/ethnicity, first language learned, and highest level of parental education. https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=171

Neufeld, J. (2025). Talent Recruitment Roulette: Replacing the H-1B Lottery. Institute For Progress. https://ifp.org/h1b/

Nezaj, J. (2024). The rise—and fall—of the software developer. ADP Research Institute. https://www.adpresearch.com/the-rise-and-fall-of-the-software-developer/

Nice, A. (2017). Wages and High-Skilled Immigration. American Immigration Council. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/wages-and-high-skilled-immigration-how-government-calculates-prevailing-wages

O’Brien, J. (2024). Tech degrees no longer guarantee a job. LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/posts/jamesfobrien_tech-jobs-have-dried-upand-arent-coming-activity-7242613292479696897-gCyT

Okeke, E. (2023). When a Doctor Falls from the Sky: The Impact of Easing Doctor Supply Constraints on Mortality. American Economic Review 113(3), 585-627. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20210701.

Ozimek, A., O’Brien, C., & Lettieri J. (2025). Exceptional by Design: How to Fix High-Skilled Immigration to Maximize American Interests. Economic Innovation Group. https://eig.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Exceptional-by-Design.pdf

Prato, M. (2022). The Global Race for Talent: Brain Drain, Knowledge Transfer, and Growth. https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/35e299dda0bce4645403a3418356b405-0050022023/original/prato-global-race-talent-november2022.pdf

Ruiz, N. & Krogstad, J. M. (2018). East Coast and Texas metros had the most H-1B visas for skilled workers from 2010 to 2016. Pew Research. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2018/03/29/h-1b-visa-approvals-by-us-metro-area/

Smith, N. (2024). Indian immigration is great for America. Substack. https://www.noahpinion.blog/p/indian-immigration-is-great-for-america

Staklis, S., & Horn, L. (2012). New Americans in Postsecondary Education. National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2012/2012213.pdf

University of Minnesota (2024). Medical device industry cluster has statewide impact. https://tpec.umn.edu/news/medical-device-industry-cluster-has-statewide-impact

USCIS (2005). Immigrant Petition for Alien Worker as an Alien of Extraordinary Ability. https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/err/B2%20-%20Aliens%20with%20Extraordinary%20Ability/Decisions_Issued_in_2005/OCT272005_02B2203.pdf

USCIS (2008). H-1B Benefit Fraud & Compliance Assessment. https://lawandborder.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/10/h-1b-benefit-fraud-assessment.pdf

USCIS (2017). Definition of “Affiliate” or “Subsidiary” for Purposes of Determining the H-1B ACWIA Fee. https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/memos/2017-8-9-PM-602-0147-H-1BAffiliateSubsidiary.pdf

USCIS (2020). H and L Filing Fees for Form I-129, Petition for a Nonimmigrant Worker. https://web.archive.org/web/20200726034602/https://www.uscis.gov/forms/all-forms/h-and-l-filing-fees-for-form-i-129-petition-for-a-nonimmigrant-worker

USCIS (2024a). FAQs for Individuals in H-1B Nonimmigrant Status. https://www.uscis.gov/working-in-the-united-states/temporary-workers/h-1b-specialty-occupations/faqs-for-individuals-in-h-1b-nonimmigrant-status

USCIS (2024b). Chapter 5 - Job Portability after Adjustment Filing and Other AC21 Provisions. https://www.uscis.gov/policy-manual/volume-7-part-e-chapter-5

USCIS (2024c). Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers. https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/reports/OLA_Signed_H-1B_Characteristics_Congressional_Report_FY2023.pdf

Wu, A. (2018). Skilled Immigration and Firm-Level Innovation: The U.S. H-1B Lottery. https://mackinstitute.wharton.upenn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/FP0185_WP_Feb2018.pdf

The H-1B visa also is given to foreign fashion models.

The full list of occupation codes that a company may submit in the I-129 petition is described by Form M-746. Notice that the occupation codes corresponding to “Cashier” (211) and “Janitor” (382) are not present in the list of eligible codes.

A common misconception is that H-1B workers must be paid the higher of $60k/year or the prevailing wage.

Legally speaking, this claim is incorrect. The $60k/year standard is used to determine whether an H-1B worker is exempt (Department of Labor 2008b). This designation is only relevant to firms which are H-1B dependent (i.e. >15% of the workforce holds an H-1B visa) or a willful violator (i.e. firms which have run afoul of H-1B regulations in the past).

Normally, these types of firms are held to additional standards during the visa application process. However, if they intend to hire an H-1B employee for at least $60k/year, then the corresponding application is no longer subject to such additional standards. In other words, an H-1B exempt worker is simply a worker which allows H-1B dependent employers/willful violators to be exempt from additional scrutiny.