Is the H-1B visa lottery truly random?

Constructively critiquing a viral post which claims otherwise

Table of Contents

Introduction

A few weeks back, a viral post by venture capitalist Debarghya “Deedy” Das caught my attention. Using a novel dataset obtained by Bloomberg on the universe of H-1B lottery registrations during the 2021-2024 fiscal years, Das claims to have shown that the H-1B lottery systematically favors certain nationalities, companies, and age groups.

If true, such a claim would indeed be shocking. The H-1B visa lottery is viewed by millions of skilled workers across the globe as providing a golden ticket to prosperity in the United States. Furthermore, this claim would undermine the entire body of economic literature which leverages the H-1B visa lottery to estimate the causal impact of skilled immigrants on businesses (Clemens 2013; Dimmock, Huang, and Weisbenner 2021; Doran, Gelber, and Isen 2022; Mahajan et al 2024). Put simply, if it were the case that the lottery systematically favored certain groups over others despite the government’s assurances to the contrary, it would be a scandal of great proportions.

The goal of this article, then, is quite simple: assess whether Das’ analysis is capable of supporting his key claims and ultimately, determine whether or not the H-1B visa lottery is truly random.

The H-1B Lottery Process

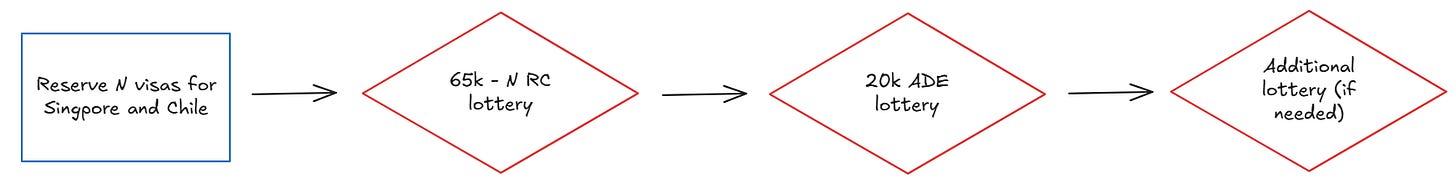

Before we can assess the strength of Das’ evidence, we must first take a moment to understand exactly how the H-1B visa lottery works.1 The H-1B visa lottery actually consists of two lotteries: the Regular Cap (RC) lottery and the Advanced Degree Exemption (ADE) lottery (Department of Homeland Security 2019).

The RC lottery is used to distribute 65k visas to skilled workers regardless of degree level. In other words, success in the RC lottery does not depend on whether one has a bachelor’s vs graduate degree. Note that a small percentage of these visas are reserved for Singaporean and Chilean applicants via the H-1B1 visa program. This quota is a known advantage that arose as a result of free trade agreements between the US and the aforementioned countries (Office of the United States Trade Representative 2003).

The ADE lottery is used to distribute 20k visas to skilled workers with a graduate degree obtained in the United States. Importantly, this means that US advanced degree-holders have two chances to win the H-1B visa lottery: the RC lottery and the ADE lottery (if they don’t already win in the RC lottery).

In the event that the RC lottery and/or ADE lottery are not projected to yield a sufficient # of visas to meet the 65k and 20k caps respectively, USCIS will conduct an additional lottery (USCIS 2024b). This four-stage process can be visualized like so:

Confounding by Degree Level

Now that we have an understanding of how the H-1B visa lottery works, we can spend some time assessing the strength of Das’ analysis. Das presents multiple charts in defense of his claim that the H-1B visa lottery is non-random. For example, he presents the following analysis of 2024 lottery data as evidence that the H-1B visa lottery is non-random with respect to nationality.2

An initial objection one might raise with this evidence is that, in any given year, we should expect some countries to have higher lottery win rates than others purely by random chance. Thus, the fact that some countries have higher win rates than others in a given year does not, in and of itself, prove that the lottery is discriminatory.

However, this objection ultimately does not pass the sniff test. In my replication of Das’ analysis, I find that certain countries consistently have higher win rates than others across lottery years. This behavior is unlikely to explained due to random chance variation alone.

This consistency is also present in lottery trends with respect to company …

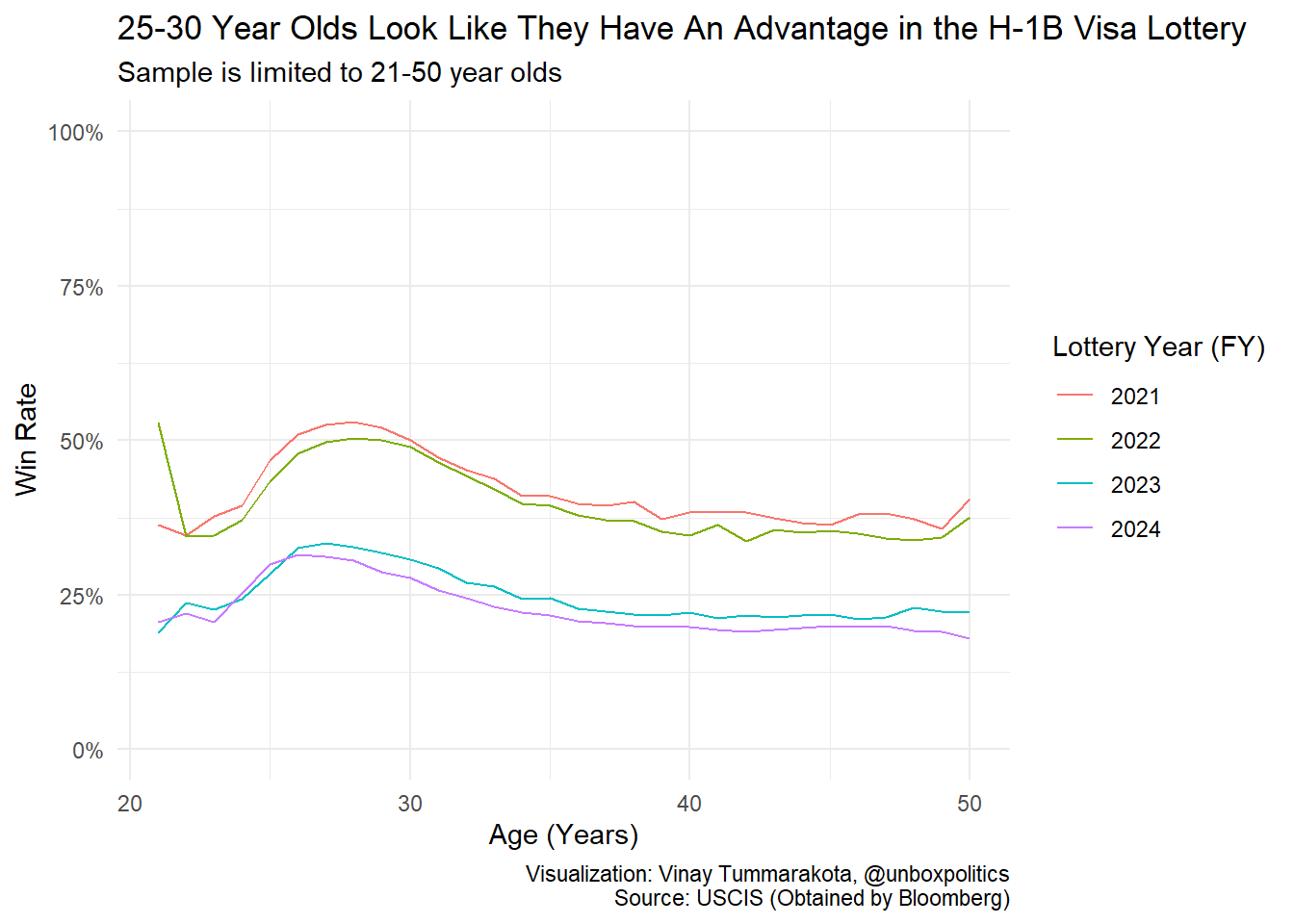

and with respect to age.

The better objection to Das’ claim, in my opinion, is that he does not take into account that level of the degree held by each applicant in the lottery. As I noted earlier, the H-1B visa lottery is intentionally non-random with respect to degree level: applicants with an advanced degree obtained in the United States have a higher probability of winning relative to non-advanced-degree-holders. Thus, the patterns identified by Das may very well be confounded by degree level:

Chinese applicants could be more likely to have advanced degrees.

Applicants to Amazon, Google, and Microsoft could be more likely to have advanced degrees.

Applicants aged 25-30 years old could be more likely to have advanced degrees.

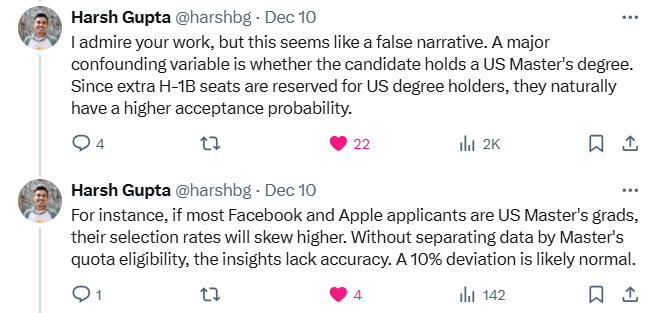

Funnily enough, other individuals have raised this issue in replies to Das.

Das responded to this objection by pointing out some companies still punch well above their weight in the lottery relative to what one would intuitively expect based on the company’s percentage of accepted applicants with an advanced degree (key word: accepted).

However, this response is mathematically unsound, and to see why, we can make use of Bayes Theorem.

To begin, let us note that the claim “the H-1B visa lottery is non-random” can be mathematically expressed like so:

In plain language, the probability that an applicant with degree d wins the lottery depends on what group (i or j) they belong to. In this setting, a group could be equivalent to a particular nationality, company, or age demographic.

By Bayes Theorem, this quantity can be expanded like so:3

The key challenge is that we do not know P(degree_{d} | group_{i}) - the probability that an individual in group i has degree d - because we do not have data on the # of all applicants in each group that obtained a graduate degree from a US institution.

The Bloomberg-USCIS dataset only contains data on degree level for a subset of lottery winners, and even at that, it only reports the degree level and not whether the degree was obtained from a US institution. Thus, unless anyone has a clever idea to overcome this limitation, I don’t think it’s possible to test for non-randomness using this data.4

Gaming The System

While Das does not satisfyingly address confounding by applicant degree level, he does raise an interesting point related to duplicate lottery entries later in his response to Gupta.

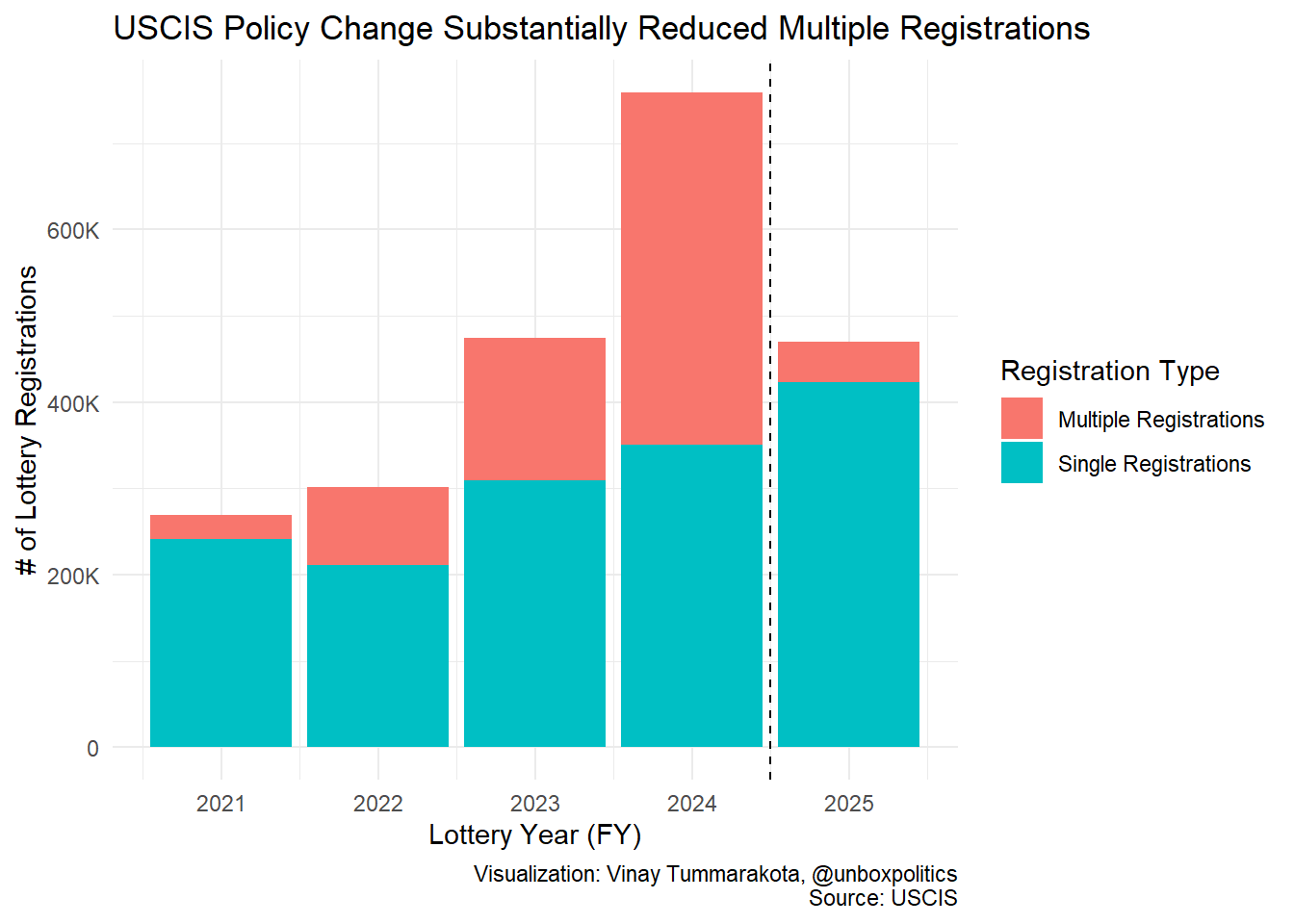

Das points out that part of the reason why lottery win rates have decreased over time is due to an increase in multiple registrations. These registrations take place when an individual applicant has secured visa sponsorship from multiple companies, thereby allowing them to enter the H-1B visa lottery multiple times. While multiple registrations are, in principle, designed to advantage highly sought-after candidates, they have unfortunately been abused by companies seeking to rig the lottery system in their favor (Fan et al 2024).

Importantly, multiple registrations are not randomly distributed with respect to nationality …

or with respect to age.

Thus, while the lottery may be random with respect to individual registrations, Das is right to intuit that it is likely not random with respect to individual applicants. Where he goes wrong, however, is in assuming that such non-randomness is driven by discrimination.

The reality is far more banal: by lowering the cost to enter the lottery and randomizing the lottery at the level of individual registrations, USCIS naturally set up the system to be gamed by unscrupulous actors.

Perhaps the one silver lining in this debacle is that, in the fiscal year 2025 H-1B lottery, USCIS acknowledged this issue and chose to randomize lottery wins at the level of individual applicants, leading to a large decrease in the volume of multiple registrations (USCIS 2024a).

Thus, while past years’ lottery were certainly gameable, prospective applicants need not worry about this type of behavior moving forward (*knock on wood*).5

Conclusion

With all of this analysis in mind, we can now revisit the original questions which motivated this article:

Are Das’ claims about the H-1B lottery substantiated?

Is the H-1B lottery truly random?

My answer is “no” to (1) and “it depends” to (2). Das’ claim that the lottery systematically discriminates against individuals on the basis of nationality, employer, and age is unsubstantiated because he cannot rule out confounding by degree level.

However, whether or not the broader allegation of non-randomness holds depends on two variables: (a) the unit of analysis one is interested in (b) the lottery year. If one is solely interested in randomness with respect to individual applicants, then multiple past H-1B lotteries were not truly random due to multiple registrations.

But if one is interested in randomness with respect to individual registrations, then the question remains an open one until the necessary data can be made available. To put my 2¢ on the table though, my prior is that these lotteries likely were random with respect to registrations given that non-random behavior has never previously been detected by the existing body of econometric literature on the H-1B visa.6

Speaking of which, what exactly does that literature have to say about the H-1B visa? Does it reveal that the H-1B program suppresses native wages and employment? Does it demonstrate that the program improves innovation and the wider economy? Does it support the contention that we should just outright abolish the program? Stay tuned for my next article to learn the answers to these questions!

All code used to create the visualizations in this article can be accessed in this GitHub repository.

Works Cited

Clemens, M. A. (2013). Why Do Programmers Earn More in Houston than Hyderabad? Evidence from Randomized Processing of US Visas. American Economic Review, 103(3), 198–202. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.3.198

Department of Homeland Security (2019). Registration Requirement for Petitioners Seeking To File H-1B Petitions on Behalf of Cap-Subject Aliens. Federal Register. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/01/31/2019-00302/registration-requirement-for-petitioners-seeking-to-file-h-1b-petitions-on-behalf-of-cap-subject

Dimmock, S. G., Huang, J., & Weisbenner, S. J. (2022). Give Me Your Tired, Your Poor, Your High-Skilled Labor: H-1B Lottery Outcomes and Entrepreneurial Success. Management Science, 68(9), 6950–6970. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2021.4152

Doran, K., Gelber, A., & Isen, A. (2022). The Effects of High-Skilled Immigration Policy on Firms: Evidence from Visa Lotteries. Journal of Political Economy, 130(10), 2501–2533. https://doi.org/10.1086/720467

Fan, E., Mider, Z., Lu, D., & Patino, M. (2024). How Thousands of Middlemen Are Gaming the H-1B Program. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2024-staffing-firms-game-h1b-visa-lottery-system

Mahajan, P., Morales, N., Shih, K., Chen, M., & Brinatti, A. (2024). The Impact of Immigration on Firms and Workers: Insights from the H-1B Lottery. Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. https://doi.org/10.21144/wp24-04

Office of the United States Trade Representative (2003). Chile and Singapore FTAs: Temporary Entry of Professionals. https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/fact-sheets/archives/2003/july/chile-and-singapore-ftas-temporary-entry-profes

USCIS (2024a). H-1B Electronic Registration Process. https://www.uscis.gov/working-in-the-united-states/temporary-workers/h-1b-specialty-occupations/h-1b-electronic-registration-process

USCIS (2024b). USCIS Will Conduct Second Random Selection for Regular Cap from Previously Submitted FY 2025 H-1B Cap Registrations. https://www.uscis.gov/newsroom/alerts/uscis-will-conduct-second-random-selection-for-regular-cap-from-previously-submitted-fy-2025-h-1b

I specifically describe how the lottery worked in fiscal years 2021-2024 as this is the time period contained in the Bloomberg-USCIS dataset.

The interested reader may click on the linked tweet to set the full thread of charts. On a different note, Singapore does not have a 100% acceptance rate because the Bloomberg-USCIS dataset excludes H-1B1 visa applicants.

Dimmock, Huang, and Weisbenner (2021) circumvent the issue of missing degree level data by leveraging industry-city-year fixed effects. In particular, they state:

We examine the PWD [prevailing wage determination] data and find that the baseline fixed effects we include in our regressions absorb much of the variation in applicant education. Specifically, industry-city-year fixed effects explain 73% of the variation in whether an applicant has a graduate degree.

I conduct a similar exercise using the subset of the Bloomberg USCIS data which reports applicant degree level (the lottery winners). Ultimately, I find that industry-city-year fixed effects can explain, at most, 23% of the variation in whether a lottery winner has an advanced degree. Thus, I’m worried that this approach will not work well in our context.

I also considered carrying out a simple bounding exercise which asks the question:

In a given lottery year, by how much would group i have had to increase their share of advanced degree applicants to have seen a win rate equal to that of group j?

The intuition behind this question is that we have information on the following quantities:

P(degree | win, group): The probability that lottery winners in a given group have a graduate degree obtained from a US institution.

P(win | group): The probability that lottery applicants in a given group win the lottery.

Using basic algebra, we can then estimate the ratio of advanced degree applicants between the different groups under the assumption that the lottery is fair.

Should this approach yield wildly implausible values (e.g. “Chinese applicants are 100x more likely to hold advanced degrees than Indian applicants”), we will have strong reason to suspect non-randomness in the lottery.

But alas, even this approach is not feasible because the dataset technically only contains degree level information on a subset of lottery winners. Given that there may be systematic reasons why some lottery winners have missing degree level information while others don’t, I would be very cautious in employing this bounding approach without further context.

fentasyl argues that shady behavior is still taking place:

First, it’s worth pointing out that total application volume decreased by 300k since USCIS implemented randomization at the level of individual applicants. Thus, the new policy has undeniably reduced the volume of fraudulent applications even if it did not wholly eliminate them. Second, USCIS could crack down on this behavior by simply fuzzy matching applicants along name, date of birth, and passport ID. Any suspicious pings could then undergo manual review to confirm duplication.

Clemens (2013) states:

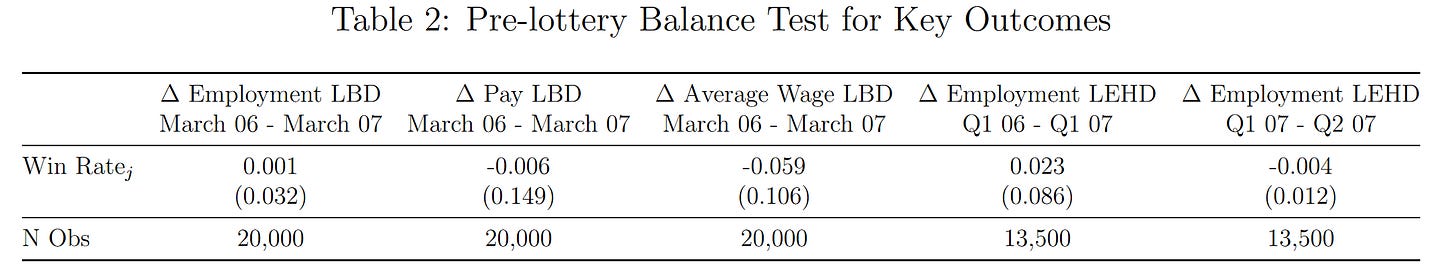

There is strong evidence of true natural randomization [in the regular cap lottery]. First, applications that lost the lottery were returned unopened, so the government had little chance to pick winners. Second, all available pre-lottery traits of winners and losers are well balanced.

Dimmock, Huang, and Weisbenner (2021) state:

Consistent with H-1B visa lottery outcomes being random, we fail to find that lottery outcomes are significantly related to firm and application characteristics.

Doran, Gelber, and Isen (2022) state:

Appendix table 6 verifies the validity of the randomized design by regressing variables that should not be affected by the lottery on chance lottery wins. The table confirms that none of the lagged dependent variables is significantly (or jointly) related to chance lottery wins. Employee characteristics … are also individually and jointly insignificantly related to lottery wins.

Mahajan et al (2024) state:

We also perform more targeted balance checks to assess the scope for pre-lottery shocks by unconditionally regressing pre-lottery changes in firm outcomes on their win rate …

If you want to sense-check the figures, IIE has data on international students in the US by nationality and level of study. If the main factor is really students with advanced degrees from US universities, dividing the number of graduate students by H1B applicants of each nationality should give a roughly similar ranking to the country-level success rates.

Adding a link would probably get my comment filtered, but the page title is: IIE Open Doors / Academic Level and Places of Origin