Same-Sex Parenting: Examining the "No Differences" Hypothesis

The best available evidence consistently provides little reason to doubt the parenting ability of same-sex couples.

Table of Contents

Introduction

“As all parties agree, many same-sex couples provide loving and nurturing homes to their children, whether biological or adopted. And hundreds of thousands of children are presently being raised by such couples … Most States have allowed gays and lesbians to adopt, either as individuals or as couples, and many adopted and foster children have same-sex parents … This provides powerful confirmation from the law itself that gays and lesbians can create loving, supportive families.”

- Justice Anthony Kennedy (Obergefell v Hodges)

On June 26th, 2015, Obergefell v Hodges granted same-sex couples the legal right to marry and established this right as the law of the land. The majority opinion written by Justice Anthony Kennedy passionately defended the right to same-sex marriage on a four key grounds: the ever-lasting bonds inherent to a two-person union, the value of individual autonomy, the injustice of denying same-sex couples equal participation in society, and the love experienced by children of same-sex parents. While each of these defenses is worthy of an essay in their own right, the final of these defenses is of particular interest to me because of its uniquely empirical nature.

You see, in the lead up to the decision, the court received two amicus briefs (among over a hundred), each of which made vastly differing claims about the efficacy of same-sex parenting.

The American Sociological Association (ASA) endorsed a view known as the “no differences” hypothesis. They asserted that the overwhelming body of literature revealed no evidences of differences in outcomes between children raised by same-sex parents and those raised by opposite-sex parents (Manning, Fettro, and Lamidi 2014).

The American College of Pediatricians (not to be confused with the American Academy of Pediatrics) asserted that both a mother and father were necessary for the development of the child. Consequently, they viewed the legalization of same-sex marriage as an endorsement of a false equivalence between an inferior same-sex family structure and superior opposite-sex family structure (Sullins, Regnerus and Marks 2015).

Both parties presented evidence in defense of their theses and offered methodological critiques of the other’s position. But ultimately, after reviewing the evidence in its totality, the court found the ASA to have made the more persuasive case and lent its legal imprimatur to the “no differences” hypothesis. Thus, the court helped to solidify the parenting rights of same-sex couples that remain in place to this day.

Based on these events, I suspect the average reader might question why I’d be interested in reviving the conversion about same-sex parenting back from the dustbin of history. One might reasonably ask:

Everyone had their chance to submit evidence to the court, the court made a decision, the gays got their rights, and everyone lived happily ever after. So why are we bringing this issue up again?

However, I think it’s important to revisit the topic of same-sex parenting for two reasons:

Eight years have passed since Obergefell v Hodges was originally decided. In that time, lots of fascinating research has come out (pun intended) on the topic of same-sex parenting.

Anti-LGBT discrimination appears to have risen in recent times. Jones (2023) finds that attitudes towards same-sex couples have taken a downturn from the previous year, largely driven by Republicans’ views on the morality of same-sex relationships.1

Because of these observations, this essay reviews the more recent body of work that has examined the “no differences” hypothesis in same-sex parenting. By doing so, I aim to demonstrate that the court, through Obergefell v Hodges, made the correct decision in affirming the rights of same-sex couples to raise children.2

Methodological Challenges

Before directly discussing the studies themselves, it’s worth understanding the large number of hurdles that researchers face when attempting to estimate the causal effect of same-sex parenting on children’s wellbeing. These hurdles come in a variety of forms as described below.

Statistical Power

Statistical power refers to the ability of a study to register an effect as statistically significant if there is, in fact, a real effect to be detected. In the context of this essay, I’m primarily concerned with whether or not a study has sufficient power to detect the effects of same-sex parenting, assuming such effects actually exist.

The reason we ought to be concerned with power is because studies of same-sex parenting often examine very small samples of same-sex parents, owing to the small fraction of the population that is gay. This issue is compounded by the fact there are substantially fewer gay fathers than lesbian mothers due to the higher costs of surrogacy relative to artificial insemination. Thus, many studies of same-sex parenting might find “no differences” in children’s outcomes only because the study lacked the power/sample size to actually detect the effects of same-sex parenting.

Unrepresentative Samples

Because same-sex parents have historically been very few and far between, many early studies of the “no differences” hypothesis examined samples of same-sex parents that were quite niche (e.g. parents at a particular clinic). This meant that the results of such studies couldn’t necessarily be generalized to the broader population of same-sex parents. To overcome this issue, a more recent wave of studies have begun to rely on nationally representative samples to approximate the causal effect of parental sexual orientation on children’s wellbeing.

Identifying Same-Sex Parents

Because most nationally representative surveys have historically not asked parents to report their sexual orientation, many studies of the “no differences” hypothesis have had to infer parental sexual orientation based on whether the two partners in a relationship are of the same sex. Though this strategy initially might seem foolproof, it fails to account for idiosyncratic respondent errors.

To elaborate, any kind of survey is bound to have some share of respondents who click the wrong button or type the wrong key when answering a question. Typically, these errors are negligible since they’re often random in nature and vastly outweighed by the number of people who do correctly fill out the survey. But these errors become a problem when examining small populations like same-sex parents. If even a small share of opposite-sex parents accidentally click the wrong button to indicate the sex of their partner, a large share of “same-sex parents” will actually consist of opposite-sex parents who entered the wrong survey response. This very issue forced the 2000 Census to retract its estimates of the share of the population that were in gay relationships (Black et al 2006).

I should also note that inferring sexual orientation based on partner’s sex doesn’t account for transgender individuals in gay relationships because, within this context, sex doesn’t strictly map onto sexual orientation.

Family Formation

Because same-sex couples cannot reproduce heterosexually, the children of same-sex parents originate through one of three pathways:

The child was born as part of a prior heterosexual marriage that ended in divorce when one of the parents came out as gay/bisexual.

The child was adopted by same-sex parents.

The child was conceived by same-sex parents via assisted reproductive technology (e.g. surrogacy, artificial insemination).

This fact creates substantial problems for analyses of the causal effect of same-sex parenting. If one simply performs a naïve comparison between children of same-sex parents and children of opposite-sex parents, they might very well find different outcomes between the two. However, this finding wouldn’t necessarily reflect differential parenting efficacy between same-sex parents and opposite-sex parents. Rather, it could simply reflect the effects of prior divorce, abandonment prior to adoption, or fertility treatment.

The most common strategy to deal with this issue to explicitly control for family formation when modeling the relationship between same-sex parenting and children’s wellbeing (Rosenfeld 2015; Potter and Potter 2017; Kabatek and Perales 2021). The idea behind this strategy is to approximate an apples-to-apples comparison between children with the same family histories. For example, researchers might:

Compare children of same-sex parents who have experienced n number of family transitions to children of opposite-sex parents who have also experienced n number of family transitions.

Compare children adopted by same-sex couples to children adopted by opposite-sex couples.

Compare children born to same-sex couples via assisted reproductive technology to children born to opposite-sex couples.

This strategy certainly has an obvious intuitive appeal since it compares outcomes between children with the same family history. But Mazrekaj, DeWitte, and Cabus (2020) point out that it may lead to a phenomenon known as post-treatment bias. This bias occurs when researchers accidentally control for variables that are themselves caused by the treatment in question. If that explanation sounds a bit abstract, don’t worry. I describe three hypothetical (but theoretically plausible) cases of post-treatment bias below:

Controlling for Adoption Status Induces Post-Treatment Bias

Let’s suppose that same-sex parents face discrimination in the adoption process.

If same-sex parents face discrimination in the adoption process, they would need to be less selective when deciding which child they would like to adopt (to maximize the chances of approval for the adoption).

Older children are often overlooked in the adoption process due to their age. But because same-sex parents are less selective in the adoption process, they would be more likely to adopt children at older ages than opposite-sex parents.

Let’s suppose that children adopted at older ages tend to have worse behavioral issues than children adopted at younger ages.3

Because same-sex parents are more likely to adopt children at older ages and these children tend to have more behavioral issues, we would expect children adopted by same-sex parents to, on average, have higher rates of behavioral issues than children adopted by opposite-sex parents.

Because higher rates of behavioral issues are interpreted as evidence of worse parenting, these results would (erroneously) imply that same-sex parenting is worse for adopted children than opposite-sex parenting.

Thus, controlling for adoption status yields a biased estimate of the causal effect of same-sex parenting.

Controlling for Prior Family Transition Induces Post-Treatment Bias

Let’s suppose that the negative effects of parental divorce on a child’s wellbeing are magnified when the the child perceives the divorce in question to be highly unexpected.4

Now consider divorce caused by a parent coming out as gay. This type of divorce is a highly unexpected event because the child was likely unaware of their parent’s true sexual orientation prior to the divorce.

Because divorce caused by a parent coming out as gay is a highly unexpected event, we would expect divorce to have a larger negative effect on the wellbeing of children with a gay parent relative to children with straight parents.

Because the larger negative effect of divorce is interpreted as evidence of worse parenting, these results would (erroneously) imply that same-sex parenting is worse for children who experienced a prior divorce relative to opposite-sex parenting.

Thus, controlling for prior family transitions yields a biased estimate of the causal effect of same-sex parenting.

Isolating the Sample to Just Birth Children Induces Post-Treatment Bias

Let’s assume that same-sex parents are more likely to make use of assisted reproductive technology than opposite-sex parents.

Let’s assume that parents have the ability to screen for desirable genetic qualities when utilizing assisted reproductive technology.

Because children born to same-sex parents are much more likely to have been screened for genetically desirable qualities, we would expect the birth children of same-sex parents to have better outcomes than the birth children of opposite-sex parents.

Because better outcomes are interpreted as evidence of better parenting, these results would (erroneously) imply that same-sex parenting is better for birth children than opposite-sex parenting.

Thus, isolating the sample to just birth children yields a biased estimate of the causal effect of same-sex parenting.

Post-treatment bias ultimately demonstrates the shortcomings of accounting for family formation by simply tacking on a few more control variables to our model. This issue unfortunately places researchers in a pretty tough bind. If, for example, researchers don’t control for adoption status, then they’ll be making an apples-to-oranges comparison between children who were adopted by same-sex parents and children who were born to opposite-sex parents. But if they do control for adoption, then they’ll be making an apples-to-oranges comparison between children who were adopted by same-sex parents at an older age to children who were adopted by opposite-sex parents at a younger age. It’s like a never ending game of statistical whack-a-mole!5

I suspect a critical reader might react to this whole dilemma by suggesting that researchers add even more controls to the model. “Let’s just control for age at adoption in addition to adoption status!” they might exclaim. I fully admit that it’s not a bad suggestion, but one issue is that this type of information isn’t always recorded in nationally representative datasets, so the idea is often a non-starter. The other issue is that this suggestion doesn’t necessarily scale well. If we want to ensure that the analysis is free from post-treatment bias, we’d have to think pretty carefully about every single way in which post-treatment bias could contaminate the causal effect of same-sex parenting and then explicitly control for such pathways. This task is easier said than done since causal relationships between variables can be quite subtle to pinpoint (exhibit a: this discussion).

Because of the intractability of this issue, most studies on the topic seem to just explicitly control for family formation knowing full well that doing so might induce post-treatment bias. The implicit argument seems to be that, if given a choice between post-treatment bias or confounding bias caused by not controlling for family formation whatsoever, it’s better to just keep the former in the equation (perhaps because it’s probably smaller in magnitude). We can think of this dilemma as the statistical analogue to choosing between the lesser of two evils.

Measuring Childhood Wellbeing

The “no differences” hypothesis asserts that children raised by same-sex parents experience no differences in outcomes relative to children raised by opposite-sex parents … but what “outcomes” are we actually talking about here?

The existing body of literature tends to focus on two types of outcomes: academic achievement and psychosocial wellbeing.

Researchers often examine academic achievement because a growing body of literature has linked high achievement to success in the labor market (Watts 2020; Koedel and Tyhurst 2012).

Researchers often examine psychosocial wellbeing because society has a vested interested in ensuring that children learn how to be well-behaved and emotionally resilient while growing up. (I hope that this should be so patently obvious as to not require a citation).

However, these two outcomes differ in at least one critical sense. While academic achievement is easily and precisely measurable via grades, academic progression, or standardized test scores, psychosocial wellbeing is … considerably less so.

Why can’t we simply ask parents about the psychosocial wellbeing of their children?

Parental assessments of childhood wellbeing don’t always conform to the assessments of their children.

De Los Reyes et al (2015) conducted a meta-analysis of 341 studies that measured parent-child correlations in children’s internalizing behaviors (e.g. anxiety, mood) and externalizing behaviors (e.g. aggressivity). They find correlations that are low-to-moderate in magnitude (r=0.28).

Augenstein et al (2022) examine the degree to which adolescent-reported depressive symptoms and parent-reported depressive symptoms predict the adolescent’s future suicidal ideation. They find that future suicidal ideation is greatest when only adolescents (and not parents) report elevated depressive symptoms.

Jones et al (2019) examine rates of concordance in reporting children’s mental health symptoms using a sample of 5,137 adolescents and their parents. They find that, among the set of adolescents who reported thoughts of killing themselves, just fifty percent of parents reported being aware of their children experiencing such emotions.

These measurement issues are also compounded by other types of biases that might emerge when relying on parental-reported mental health outcomes:

If same-sex parents are concerned about the possibility that research into parenting practices may be used against them, they might implicitly report their children’s wellbeing to be more positive than it actually is. This phenomenon is an example of social desirability bias.

If same-sex parents are more open to talking about mental health with their children, then they may be more likely to report that their child has a mental health condition, providing researchers with the false impression that children of same-sex parents have a higher rate of mental health conditions than children of opposite-sex parents. This phenomenon is an example of selection bias.

Thus, there are limitations to the conclusions that can be drawn from parental reports of children’s mental health.

Why can’t we ask children themselves?

Children can provide accurate information about their own health and wellbeing if they are surveyed in a manner that is developmentally appropriate. Bevans and Forrest (2009) highlight a few considerations:

Children may lack sufficient vocabulary to understand health-related questions.

Children may lack the ability to clearly articulate their internal emotional state to third parties.

Children may lack the focus/attentiveness to complete a health-related survey.

These problems are certainly less of an issue when surveying adolescents. But Augenstein et al (2022) posit that adolescents might minimize reports of negative mental health outcomes to avoid external intervention. Thus, exclusive reliance on children-reported mental health outcomes isn’t guaranteed to paint a wholly accurate picture of children’s mental health.

What about asking children about their psychosocial wellbeing once they become adults?

The main issue with this approach is that we can’t be sure that the negative mental health outcomes experienced by adults are necessarily attributable to their upbringing, and more specifically, the family structure in which they were raised. One might try to resolve this issue by simply asking adults to recall any kinds of traumatic events that they may have experienced during their childhood. However, Baldwin et al (2019) find that retrospective reports of childhood maltreatment often differ substantially from reports and records that are gathered at the time the maltreatment occurs. They posit a number of reasons why this might be the case:

Respondents might become convinced that the maltreatment they experienced was “not actually a form of abuse” and, as a result, not report their experiences as a form of maltreatment.

Respondents might have false memories of childhood maltreatment (perhaps due to mistaking dreams for actual experiences).

Respondents might not have registered maltreatment as such at the time it occurred because children are in a constant state of neurological development.

Thus, retrospective recollections of childhood maltreatment can only provide a limited picture of one’s family upbringing.

What about asking teachers to report children’s behavior in the classroom?

One advantage to relying on teacher report is the lack of social desirability bias. Because the behavior of the child reflects more on the child’s home environment than it does on the teacher, the teacher is free to honestly assess the child’s behavior. However, this advantage is offset by two weaknesses:

Teachers only observe students for a limited fraction of the day and duration of the year, so their assessments cannot fully capture children’s mental health.

De Los Reyes et al (2015) finds that teacher-child correlations for reports of internalizing and externalizing behavior are r=0.20 and r=0.29, respectively. These correlations are low-to-moderate in magnitude.

Thus, teacher reports of student behaviors provide limited insight into the psychological wellbeing of children.

What about measuring rates of clinical diagnosis of mental health issues?

There’s a decent chance that selection bias might undermine any inferences that can be drawn from official medical records or clinical data. If same-sex parents are more open to sending their child to a therapist, the diagnosis rate for children of same-sex parents would be higher solely because a higher share of such children would be in a position to be diagnosed in the first place.

What about measuring outcomes associated with mental health that can’t be fudged by self-report (e.g. arrest rates, teen pregnancy rates)?

This strategy certainly has a theoretical appeal. However, it would only work if you had access to arrest records (birth records) that could reliably be traced back to the sexual orientation of the arrestee’s (teen parent’s) parents. This task is clearly easier said than done given that no researcher (as far as I’m aware) has attempted to do this.

Because of the variety of issues associated with measuring children’s psychosocial wellbeing, this essay will try (key word: “try”) to highlight those studies that utilize generally reliable measures of such wellbeing.

Inadequate Controls

There are a variety of variables that one ought to control for to best approximate the causal effect of same-sex parenting. These include, but are not limited to, household income, anti-gay sentiments in the areas where the parents are raising the child, and whether the child has a disability. Because nationally representative samples don’t always include this information, researchers may not be in a position to fully control for such variables.

Key Takeaway

Absent a large-scale experiment where babies are randomly given up for adoption to same-sex parents and opposite-sex parents, it won’t be possible to fully account for all of the issues described above. However, this fact should not be taken to mean that it’s impossible to shed light on the “no differences” hypothesis. In the sections that follow, I describe a number of studies that examine the “no differences” hypothesis, each of which overcomes a substantial number of the methodological issues described in this section.

Psychosocial Wellbeing

Bos et al (2016)

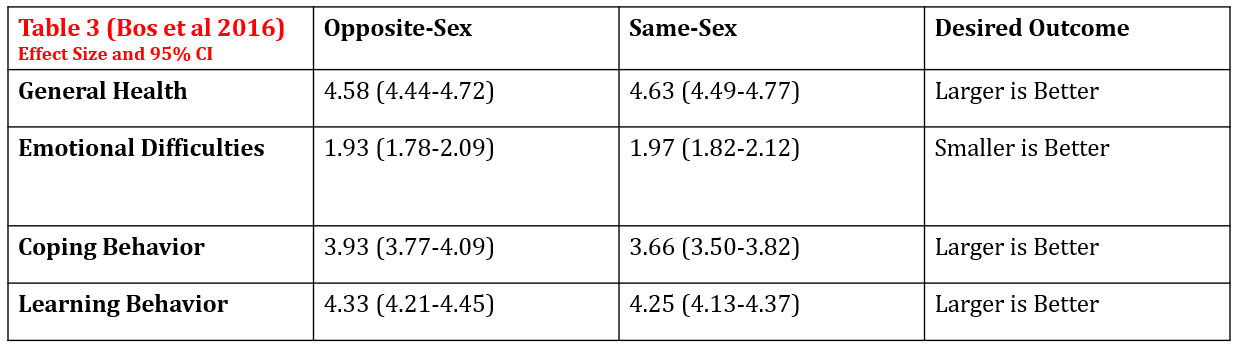

This study examines the relationship between same-sex parenting and a variety of childhood outcomes by leveraging data from the 2011-2012 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH). The study draws attention to four outcomes, each of which is measured on a 1-5 scale:

General health: Parents were asked to answer “In general, how would you describe [your child’s] health?”

Emotional difficulties: Parents were asked to specify how often during the past month their was unhappy, sad, or depressed.

Coping behavior: Parents were asked to report whether their child would stay calm and in control when faced with a challenge.

Learning behavior: Parents were asked questions about children’s learning progress such as whether they would complete homework.

The study identifies 106 children of same-sex parents using the following procedure:

The respondent and cohabiting partner both had the same gender and reported being parents of the same child.

The child had never experienced divorce or parental separation.

The child was not born to another family.

These last two criteria guarantee that the child was raised by the same-sex couple from birth (via assisted reproductive technology), ensuring that the results are completely unaffected by prior family instability. However, they might also induce post-treatment bias for the reasons discussed in the methodology section. Because there are only eight children of gay fathers that meet these criteria, the analysis solely focuses on children of lesbian mothers, leaving 98 children of same-sex couples in the final sample.

The authors create matched pairs of children of same-sex parents and children of opposite-sex parents where the pairs have children/parents of equal age, children/parents with equal citizenship status, parents with equal educational attainment, and parents living in the same geographic region. Because the NCHS doesn’t report household income or children’s disability status, the authors were unable to control for these variables. Regardless, the average outcomes of children in the matched pairs are fairly comparable:

The one exception to this trend might be the coping behavior outcome: while the difference in coping behavior is not significant, the effect is of an appreciable size (d=0.34). To explore this effect further, the authors create a regression model that adjusts for parenting stress. This adjustment reduces the magnitude of the coping behavior difference from 0.27 points to 0.06 points, suggesting that greater parenting stress among same-sex couples (perhaps due to anti-gay discrimination) may increase the challenges that children of such couples face in life.

Thus, the study is consistent with the “no differences” hypothesis across most forms of childhood wellbeing with the possible exception of coping behavior.

Potter and Potter (2017)

This study examines the relationship between same-sex parenting and teacher-reported psychosocial wellbeing. It leverages data from four waves of the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study Kindergarten Cohort (ECLS-K) which document childhood outcomes from kindergarten to fifth grade. Teachers reported psychosocial wellbeing along three different dimensions:

Externalizing wellbeing is based on how frequently a child argues, fights, gets angry, acts impulsively, and disturbs ongoing activities.

Internalizing wellbeing is based on how frequently a child acts anxious, appears lonely, exhibits low self-esteem, or seems sad.

Interpersonal skills is based on children’s ability to form and maintain friendships, get along with people who are different, comfort or help other children, express feelings and ideas appropriately, and show sensitivity toward the feelings of others.

For each wave of survey data, the authors classify children as belonging to one of the following eight family structures:

Married, two-biological parent

Divorced parent

Step-parent

Single-parent

Cohabiting parent

Widowed parent

Same-sex parent

Other (e.g., living with grandparent(s), aunt, uncle, cousins, or other nonrelative)

The authors then use the following strategy to identify 155 children who had same-sex parents during at least one survey wave:

The parents had to report that they were a mother/female guardian (father/male guardian) whose partner was also a mother/female guardian (father/male guardian), girlfriend (boyfriend), or female (male) nonrelative aged 21-49.

There were no other adults in the household whose sex was opposite that of the parent.

The study includes two measures to control for previous family instability, each of which may induce post-treatment bias for the reasons discussed in the methodology section:

The authors compute the cumulative number of family transitions by tallying the number of times a child experiences a transition between distinct family structures over the course of the previous survey waves.

The authors measure early family instability by including a variable that documents the family structure that the child belonged to during the first wave of the study.

The authors model the relationship between same-sex parenting and psychosocial wellbeing, controlling for the cumulative number of family transitions, early family instability, parental depressiveness, child’s sex, child’s race, income quintile, poverty status, whether the child spoke English at home, whether the child was starting kindergarten for the first time, and parental involvement in the child’s schooling. There are three points worth noting about these controls:

The decision to control for parental involvement in school is pretty odd since the relationship between parenting efficacy and children’s outcomes is presumably mediated by parental involvement. Put another way, it’s generally not good practice to control away the effect that you’re interested in estimating.

The authors are unable to control for anti-gay stigma against same-sex couples. This is a relevant omission since the four waves of the study span the years 1998-2004, a time when same-sex couples were not exactly viewed favorably by the public (McCarthy 2022).6

The authors are unable to control for disability status even though disability is almost certainly associated with teachers’ assessments of children’s behavior in the classroom.

Putting these limitations to the side, the model finds no statistically significant differences in externalizing behavior, internalizing behavior, and interpersonal skills between children of same-sex parents and children of married biological parents. Thus, the study appears to be highly consistent with the “no differences” hypothesis.

Before leaving with this takeaway however, there are a number of criticisms worth considering:

It’s true that the associations between same-sex parenting and psychosocial wellbeing never reach statistical significance, but these associations are consistently negative even after accounting for the number of prior family transitions. This suggests that the study lacked sufficient power to detect the negative effect of same-sex parenting.

To address the issue of statistical power, the authors lower the threshold for statistical significance to p<0.10 (as opposed to the conventional p<0.05), thereby increasing the probability of a finding turning up as significant. The effects of same-sex parenting continue to remain insignificant using the lowered threshold. This result doesn’t necessarily imply that statistical power is a non-issue, but it does provide evidence in that direction.

You seem to be ignoring the fact that same-sex parenting at kindergarten did predict significantly worse externalizing behavior (Table 3).

The problem with examining associations between same-sex parenting at kindergarten and later psychosocial wellbeing is that the authors don’t observe family transitions prior to kindergarten:

Despite the many advantages of using the ECLS-K, the data set does not provide detailed information on children’s family structure in the years prior to kindergarten, a limitation we recognize.

Thus, it’s entirely possible that the “same sex parents at kindergarten” effect is really just capturing the effect of a prior divorce of a heterosexual marriage that couldn’t be documented in the dataset.

The vast majority (90%) of the children of same-sex couples examined were children of lesbian parents, meaning the results may not generalize to gay fathers.

This is a legitimate limitation of the study.

Taking the above criticisms into consideration, the study’s consistency with the “no differences” hypothesis is mostly limited to lesbian mothers and could be limited by lack of statistical power.

Calzo et al (2019)

This study examines the relationship between having at least one gay parent and childhood wellbeing using the 2013-2015 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). Beginning in 2013, the NHIS directly asked respondents to report their sexual orientation. This property of the dataset is incredibly important for several reasons:

The measurement of the relationship between same-sex parenting and childhood outcomes can now include the effect of gay single parents. Prior studies couldn’t measure this effect because they relied on the sex of the parent’s partner to indirectly infer sexual orientation.

The authors can measure the effect of bisexual parents on childhood outcomes. Prior studies couldn’t measure this effect because they couldn’t distinguish between, say, a bisexual woman married to a straight man and a heterosexual woman married to a straight man.

The study ultimately identifies 147 children whose parents reported being gay and 149 children whose parents reported being bisexual.

The authors quantify childhood wellbeing using the Six-Item Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SF-SDQ). The SF-SDQ asks parents to describe their children’s behavior, emotional state, and social skills. Ringeisen et al (2015) demonstrate that scores obtained from the SF-SDQ can correctly identify children with diagnosable mental impairments just over half of the time.7

The authors model the relationship between being raised by a gay parent (or bisexual parent) and SF-SDQ scores, controlling for parental sex, parental educational attainment, whether the child lives with one or two parents, the region of the country where the family lives, child’s age, child’s sex, and child’s race. There are several important points to note about the control variables used:

Controlling for whether the child lives with one or two parents might induce post-treatment bias for the reasons described in the methodology section.

The authors include an additional control for parental distress to assess whether the results are attributable to the downstream effects of discrimination on parents. Interestingly, parental distress is relatively high for bisexual parents while distress is roughly equivalent between gay and straight parents. The authors surmise that this might be attributable to the experience of discrimination against bisexual individuals from both sides (i.e. from gay and straight people).

The authors don’t control for household income or whether the child is disabled even though both of these variables could easily affect the child’s psychosocial wellbeing, independent of the variables already accounted for.

The model ultimately finds no significant differences in outcomes between children of gay/bisexual parents and children of straight parents. Based on these results, the authors state:

Methods of statistical decision making, including those used in the current study, cannot prove that no differences exist (proof of the “null hypothesis”). Thus, while we tested for the existence of differences, but could not find them in some cases, we cannot prove that minor differences do not exist. However, the robustness of non-findings across different previous studies and varied study designs increasingly provides reassurance that whatever differences might exist between children raised in LGB-parented families and those raised in heterosexual families are likely to be very small if they exist at all.

Thus, the study fails to reject the “no differences” hypothesis.

Mazrekaj, Fischer, and Bos (2022)

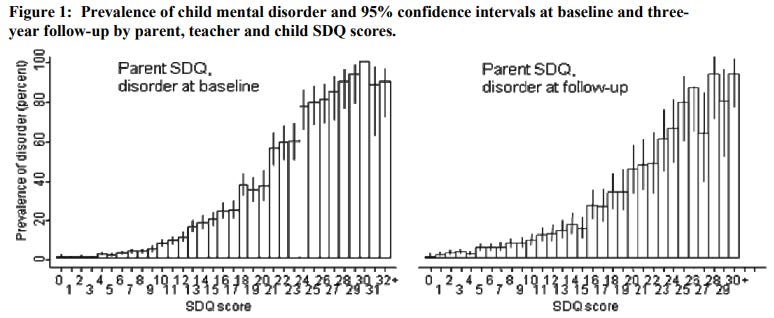

This study examines the relationship between same-sex parenting and childhood wellbeing as measured by the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). The SDQ examines childhood wellbeing along five subscales: emotional problems, conduct problems, hyperactivity, anti-social tendencies, and peer problems. Goodman and Goodman (2009) demonstrate that higher parent-reported SDQ scores are meaningfully predictive of clinician-diagnosed mental disorders:

The authors randomly sample families from Dutch population registers (and oversample same-sex parents) to create the initial dataset. They then verify the parent’s sexual orientation by asking them directly about their sex and their partner’s sex. The final sample ultimately consists of 134 households, 62 of which are headed by same-sex parents and 72 of which are headed by straight parents.

The authors create matched pairs of same-sex and opposite-sex parents who are either exactly equivalent or near equivalent in the following characteristics: child’s age, child’s sex, parental educational attainment, monthly income, marital status, whether the child was born outside of the marriage, and number of children living in the household. This decision is intended to create an apples-to-apples comparison between the matched pairs. However, controlling for whether the child was born outside of the marriage might induce post-treatment bias for the reasons discussed in the methodology section.

Putting the issue of post-treatment bias aside, the effect of same-sex parenting on childhood psychosocial wellbeing is statistically indistinguishable from zero as shown in the figure below:

I suspect that a critical reader might see this chart and think “It’s true that the effect is indistinguishable from zero, but the estimate of the effect of same-sex parenting on total problem behavior looks pretty high.” However, this assertion doesn’t withstand further scrutiny. If we think back to the graph of clinical diagnosis presented earlier, an SDQ-score increase of 0.77 points increases the probability of clinical diagnosis by a fairly negligible amount.8 Thus, the results provide little reason to worry about the efficacy of same-sex parenting.

Because the authors find no evidence of significant negative effects of same-sex parenting, the best a critic of the “no differences” hypothesis can do is to claim that the effects of same-sex parenting on childhood wellbeing are trivial in magnitude. Thus, the study fails to reject the “no differences” hypothesis.

Academic Achievement

Boertien and Bernardi (2019)

This study examines the relationship between same-sex parenting and grade retention using the 2008-2015 American Community Survey (ACS). The authors identify 7,792 children aged 8-16 who lived with same-sex parents during at least one survey wave using the following process:

The household is initially considered to have same-sex parents if the head of household and their partner are listed as having the same-sex and a child resides in the household.

Same-sex parents with outlier values (e.g. large age gaps between partners) are individually examined to verify that the household head and their partner are, in fact, both same-sex parents of the child in the household. This process identifies several multigenerational households that were erroneously documented as having same-sex parents (e.g. a household where a grandmother accidentally lists her daughter-in-law as her partner rather than her son’s partner).

The authors verify that their estimates of the share of same-sex households are consistent with other independently derived estimates that have already been vetted for accuracy.

Grade retention is computed as a joint function of the child’s age and the highest grade of schooling that the child has completed. If the child is at least 1 year greater than the two ages that are commonly associated with the grade the highest grade the child has completed, the child is documented as having experienced grade retention (e.g. 8+ years old but not yet completed first grade).

The authors create four different models to estimate the effect of same-sex parenting on grade retention. The models all control for parental educational attainment, parental age, household income, number of children in the household, whether there are additional household members (e.g. grandparents), whether the child has a disability, child’s sex, and child’s race. However, they differ in the following respects:

The first model includes the entire sample of children of same-sex parents.

The second model excludes potentially miscoded children of same-sex parents (perhaps due to multigenerational households).

The third model includes only children who lived with same-sex parents at age 8. This choice increases the probability that the child experienced grade retention when they were actually living with same-sex parents rather than under family arrangements that preceded the formation of the same-sex couple altogether.

The fourth model includes only the 1,182 children adopted by same-sex parents. This choice is designed to foster an apples-to-apples comparison between children adopted by same-sex vs opposite-sex parents. However, it may induce post-treatment bias for the reasons discussed in the methodology section.

The results of these models are unanimous: not only are there are no statistically significant differences in grade retention between children of same-sex parents and children of opposite-sex parents, but the effect of same-sex parenting on grade retention is basically zilch; whether the child is raised by same-sex parents or opposite-sex parents doesn’t seem to matter in the slightest.

The authors go one step further by examining the change in the effect of same-sex parenting on grade retention over time. Their results indicate that, while same-sex parenting was initially associated with higher probability of grade retention, this effect completely dissipated over time.

The authors posit two explanations for this dynamic:

Discriminatory environments: They find that the the effect of same-sex parenting on grade retention was higher in 2008 within: (1) areas that harbored more negative sentiments towards same-sex couples (2) states that hadn’t recognized same-sex marriages/unions by 2010. These findings suggest that the children of same-sex parents initially fared worse academically not due to the inefficacy of same-sex parenting, but rather due to the discriminatory climate in which these children were raised.9

Discrimination in the adoption process: The authors find that the effect of same-sex parenting on grade retention was initially highest for children adopted by same-sex couples. However, this effect completely dissipated over time as shown in the figure below:

This finding suggests that the initially worse outcomes of children adopted by same-sex parents was likely an artifact of post-treatment bias. If same-sex couples initially experienced discrimination in the adoption process, they would’ve been more likely to adopt children with greater behavioral issues, leading to higher rates of grade retention. But because discrimination against same-sex couples likely decreased over time, the characteristics of children adopted by same-sex couples and children adopted by opposite-sex couples likely converged, leading to no differences in grade retention in the long-run.

Because the study finds no evidence of differences in grade retention between children of same-sex parents and children of opposite-sex parents under a variety of statistical models, the study is consistent with the “no differences” hypothesis.

Mazrekaj, DeWitte, and Cabus (2020)

This study examines the relationship between same-sex parenting and eighth grade standardized test scores in the Netherlands. The authors identify 1,390 birth children of same-sex parents via the following criteria:

People who all live at the same address are defined as belonging to the same household.

Parents/stepparents are distinguished from grandparents in the same household using the personal identifying numbers (PIN) that are associated with each resident in the municipal register.

If both parents have the same-sex and the child has lived with them since birth, the child is considered a birth child of same-sex parents.

The authors model the relationship between being a birth child of same-sex parents and standardized test scores, controlling for household income, parental education, parental birth country, neighborhood residence, parent age, and family size at the time the child was born (as opposed to the time when they child took the standardized test).

The appeal of this strategy is that it compares outcomes between children whose starting point in life is approximately the same, meaning that any subsequent differences in children’s test scores are most likely attributable to differences in parental sexual orientation rather than other variables. However, this strategy may induce post-treatment bias for the reasons discussed in the methodology section. This strategy ultimately finds that same-sex parenting from birth is associated with a 13.9% (±2.3%) increase of a standard deviation in standardized test scores.

The authors verify these results using two additional empirical strategies:

Coarsened Exact Matching: The authors match each child born to a same-sex parent with a child born to an opposite-sex parent who has the exact (or near-exact) same value for each of the sociodemographic variables previously described (e.g. household income). This exercise finds that same-sex parenting from birth is associated with a 14.7% (±4.1%) increase of a standard deviation in test scores.

Cousins Fixed Effects: The authors compare outcomes between the birth children of same-sex parents and their cousins born to opposite-sex parents, a strategy that partly controls for genetically inherited components of academic aptitude. This exercise finds that same-sex parenting from birth is associated with a 10.2% (±4.1%) or 13% (±5.9%) increase of a standard deviation in standardized test scores.

The authors also expand the scope of the study to encompass children adopted by same-sex parents and children born as part of prior heterosexual marriages. They find a significant (though far smaller) positive effect of same-sex parenting on standardized test scores.

Because multiple statistical methods demonstrate that same-sex parenting from birth is associated with higher standardized test scores, the study is inconsistent with the “no differences” hypothesis, albeit for reasons that would imply the superiority of same-sex parenting.

Kabatek and Perales (2021)

Just like the prior study, this study examines the relationship between same-sex parenting and eighth grade standardized test scores in the Netherlands (albeit using different statistical methods). The authors utilize the following procedure to identify 125 children of gay fathers and 2,881 children of lesbian mothers:

They identify children living with two legal parents in the household or one legal parent and their legally recognized partner. This procedure excludes children with a single parent and children with nontraditional family forms (e.g. living with parent and grandparent).

They use birth certificates and/or municipal data banks to identify the sex of each parent. If both parents have the same sex, they are considered same-sex parents.

The authors then create three categories of control variables:

Family sociodemographic characteristics: child’s sex and adoptee status; number

of children in the household; province of residence; urbanization level; year of the standardized test, parents’ civil union status; each parent’s ethnicity, migrant background, and birth cohort.

Family socioeconomic characteristics: parental educational attainment; labor market participation; disability; and income.

Children’s life course family dynamics: the number of residential moves; the number

of changes in family structure experienced by the child prior to taking the test; initial household composition at birth.10

The model finds that same-sex parenting is associated with a statistically significant academic achievement advantage of 12 percent of a standard deviation, controlling for the aforementioned sets of variables. Remarkably, the advantage is 5 percent of a standard deviation even without controlling for children’s life course family dynamics. Thus, the results are compelling regardless of whether one views same-sex relationships as inherently stable or not.

The authors perform additional analyses to examine the robustness of these findings. These analyses find that:

Lesbian parenting is associated with positive effects on academic achievement while gay parenting has insignificant effects (though this latter result may simply be driven by low power).

Same-sex parenting is associated with significant positive effects on grade retention, enrollment in advanced academic tracks in high school, and college enrollment.

Longer exposure to same-sex parenting is associated with greater academic achievement.

Any exposure at all to same-sex parenting during childhood is associated with greater academic achievement.

Because the study demonstrate that same-sex parenting is associated with higher standardized test scores, the study is inconsistent with the “no differences” hypothesis, albeit for reasons that would imply the superiority of same-sex parenting.

The Contrarian Studies

While I regard the previously described sets of studies as having the highest quality in the existing body of literature, I would be remiss if I didn’t address the set of studies that are often plastered on conservative-leaning websites to reject the “no differences” hypothesis. This essay discusses the three most prominently cited studies, each of which relies on nationally representative samples of children with same-sex parents.

Regnerus (2012a)

This study leverages a nationally representative sample of young adults aged 18 to 39 known as the New Family Structures Study (NFSS) to examine the relationship between same-sex parenting and 40 different outcomes indicative of wellbeing (e.g. depression, drug use, sexual abuse). The NFSS identified 236 children of same-sex couples by asking respondents, “From when you were born until age 18 (or until you left home to be on your own), did either of your parents ever have a romantic relationship with someone of the same sex?”.

The author then classifies respondents into 8 mutually exclusive categories based on the family structure in which they were raised:

Intact biological families: Lived in intact biological family (with mother and father) from 0 to 18, and parents are still married at present

Lesbian mother: Reported that their mother had a same-sex romantic relationship with a woman, regardless of any other household transitions

Gay father: Reported that their father had a same-sex romantic relationship with a man, regardless of any other household transitions

Adopted: Was adopted by one or two strangers at birth or before age 2

Divorced later or had joint custody: Reported living with biological mother and father from birth to age 18, but parents are not married at present

Stepfamily: Biological parents were either never married or else divorced, and primary custodial parent was married to someone else before turning 18

Single parent: Biological parents were either never married or else divorced, and primary custodial parent did not marry (or remarry) before turning 18

All others: Includes all other family structure/event combinations, such as respondents with a deceased parent

The author then models the relationship between same-sex parenting and each of the 40 outcome variables, controlling for a variety of sociodemographic variables (e.g. parental educational attainment, household income). The model also controls for discrimination by including a measurement of the gay-friendliness of state-level policies. The results are as follows:

There are 24 statistically significant differences in outcomes between children of lesbian mothers and children of intact biological families. These differences consistently indicate worse outcomes among children of lesbian mothers.

There are 19 statistically significant differences in outcomes between children of gay fathers and children of intact biological families. These differences consistently indicate worse outcomes among children of gay fathers.

These results might initially lead one to think that the “no differences” hypothesis is obviously false. However, this assessment would be unwarranted for several reasons.

Obvious Data Errors

The survey included several responses from individuals that were clearly nonsensical. The most egregious of these were described rather hilariously by Cheng and Powell (2015):

The most blatant example of highly suspicious responses is the case of a 25 year-old man who reports that his father had a romantic relationship with another man, but also reports that the (the respondent) was 7-feet 8-inches tall, weighed 88 pounds, was married 8 times and had 8 children. Other examples include a respondent who claims to have been arrested at age 1 and another who spent an implausibly short amount of time (less than 10 minutes) to complete the survey.

The takeaway here is to actually verify that your data is consistent with reality before conducting any modelling.

Raising Children

The study claims to examine the relationship between being raised by same-sex parents and a multitude of outcomes. But Cheng and Powell (2015) point out that the vast majority of respondents described as “being raised by same-sex parents” were not, in fact, raised by a same-sex couple for a meaningful amount of time:

138 never even lived with their parent’s same-sex partner.

41 lived with their parent’s same-sex partner for a year.

35 lived with their parent’s same-sex partner for two to four years.

23 lived with their parent’s same-sex partner for at least four years.

It can hardly be said that the first three of the aforementioned categories can be counted as children “raised by” same-sex parents.

Regnerus (2012b) acknowledges this limitation but argues that limiting the sample of children raised by same-sex parents to only those in the final category would severely limit the statistical power of the study. I certainly grant that this would be the case, but a lack of statistical power is no excuse for shoehorning respondents into categories to which they don’t actually belong.

The Creation of Family Structure Categories

The study separates respondents into 8 mutually exclusive family structures despite the fact that children of same-sex couples may belong to multiple different family structure categories. The author defends this choice by claiming it will increase statistical power:

These eight groups are largely, but not entirely, mutually exclusive in reality. That is, a small minority of respondents might fit more than one group. I have, however, forced their mutual exclusivity here for analytic purposes. For example, a respondent whose mother had a same-sex relationship might also qualify in [divorced parent] or [single parent], but in this case my analytical interest is in maximizing the sample size of [lesbian mothers] and [gay fathers] so the respondent would be placed in [lesbian mothers].

I will re-emphasize that statistical power is not an excuse to create misleading groups of family structures. By the author’s own admission, the plurality of respondents dubbed “children of same-sex parents” were born as part of previously dissolved heterosexual marriages:

Although the NFSS did not directly ask those respondents whose parent has had a same-sex romantic relationship about the manner of their own birth, a failed heterosexual union is clearly the modal method: just under half of such respondents reported that their biological parents were once married.

Because the sample of children of same-sex couples necessarily has a higher rate of divorce, any analytic strategy which ignores this fact is bound to yield misleading results.

Regnerus (2012b) responds to this criticism in two ways:

The author argues that adjusting for family instability in same-sex relationships is improper because instability represents a key pathway through which same-sex relationships harm children’s wellbeing. Regnerus (2015) clarifies:

I could very probably erase the association between exposure to Agent Orange and cancer in Vietnam veterans, if I were able to control for sustained exposure to heavy forestation in combat zones (meaning, areas most apt to be treated with the chemical). Every shaping influence has a pathway by which it does its work. “Control for” those pathways and—bingo—that influence no longer appears to matter.

This response, however, seems to betray a misunderstanding of causality. Kabatek and Perales (2021) point out that it would be nonsensical to attribute negative childhood outcomes to the “inherent instability of same-sex unions” if these outcomes were instead attributable to the dissolution of a heterosexual marriage that preceded the formation of the same-sex union altogether. In other words, you can’t confuse a resulting symptom with its underlying cause. Rosenfeld (2015) also highlights that the plurality of family transitions experienced by children with a gay parent in the NFSS were not breakups between that parent and their same-sex partner. Rather, they were custody losses. Because support for same-sex marriage was low during the childhood of most respondents, it’s plausible to think that this custody loss is largely attributable to anti-gay discrimination (i.e. believing that gay parents should lose custody because gay people are inherently unfit to raise kids).11

The author compares children of same-sex parents directly to alternative family structures (e.g. stepfamily, single parents, divorced parents). Because this comparison finds that children of same-sex parents still fare worse than children of divorced parents, the author argues that divorces of prior heterosexual unions cannot explain away the difference in outcomes between children raised by same-sex parents and children raised by opposite-sex parents. However, this inference is erroneous because of the post-treatment bias discussed in the methodology section and because of the multiple hypothesis testing considerations described below.

Multiple Hypothesis Testing

The multiple hypothesis testing problem occurs when researchers test an incredibly large number of hypotheses about the data, leading statistically significant relationships to emerge by chance alone. Note that the original study examines 40 different outcomes among 8 types of family structures using 2 statistical methods (bivariate t-tests and multi-variate models). This amounts to 640 hypothesis tests! Using a statistical significance threshold of 0.05, we would expect 32 of these hypothesis tests to yield statistically significant results purely by chance.

Insufficient/Incorrect Controls

Cheng and Powell (2015) argue for the inclusion of a greater set of control variables including but not limited to: whether the child received welfare growing up, the age of the biological mother and father at time of birth, and the residential area where the child lived.

Rosenfeld (2015) argues that the study’s attempt to control for state-level policies towards gay individuals is confused because state-wide policies changed substantially during respondents’ childhood and cannot be appropriately captured using a single point-in-time metric.

The above issues ultimately call into question the conclusions about same-sex parenting that one can reasonably derive from this study.

Allen (2013)

This study examines the relationship between same-sex parenting and high school graduation rates using the 2006 Canadian Census. There are two main benefits to relying on data from this census:

The census identifies roughly 1,400 children of same-sex parents who were either married or a common law couple at the time of the survey. This large sample alleviates concerns about statistical power.

In 1997, same-sex couples in Canada secured the right to an equivalent set of legal benefits as opposite-sex couples. In 2005, the Canadian government legalized same-sex marriage. Because the same-sex couples in this dataset had a legal status that was comparable to that of opposite-sex couples, we can have more confidence that discrimination is not confounding the analysis.

The author subsets the data to include only children aged 17-22 who were currently living with their parents at the time the census was administered. Among this subset of the data, the author models the relationship between parental sexual orientation and whether the child has graduated high school, controlling for a variety of sociodemographic variables (e.g. parental educational attainment, household income). The model yields the following results:

The point estimates for high school graduation show that there is a significant reduction in the odds of children living in same-sex homes completing high school. In the case of gay parents, children are estimated to be 69% as likely to graduate compared to children from opposite sex married homes. For lesbian households the children are 60% as likely to graduate from high school.

Based on these results, one might have serious doubts about the efficacy of same-sex parenting. However, Cohen (2013) draws attention to a form of selection bias that poses a substantial threat to the integrity of the study. The author focuses solely on children currently living with parents at the time the census was administered. But this population is almost certainly unrepresentative of the full sample of young adults aged 17-22.

Think about the population like this: Here are some possible scenarios for 17-22 year-olds. The “live at home” column represent the people in Allen’s sample; the “doesn’t live at home” column represents threats to the validity of his sample. If the distribution across these columns is correlated with family structure, the study is wrong. What are the odds?

The basic point is that a substantial share of high school graduates are likely not living at home with their parents because they are successfully employed, attending college away from home, or enlisting in the military. Because the study cannot speak to the graduation rates of this (arguably more important) population, its claims about graduation rates are utterly uninformative.

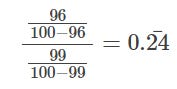

Cohen (2013) also points out that the author’s communication of results in the abstract and in popular media is rather confusing. The author prominently touts results like “Children living with gay and lesbian families in 2006 were about 65% as likely to graduate compared to children living in opposite sex marriage families.” This metric sounds as though it’s a ratio between the graduation rate of same-sex households and opposite-sex households, but it isn’t. This metric is actually the odds ratio which carries an altogether different interpretation. Cohen (2013) provides the following example to illustrate the difference:

Let’s suppose that children of same-sex parents had a graduation rate of 96% and children of opposite-sex parents had a graduation rate of 99%. The ratio of graduation rates would have the following value:

But the odds ratio would have the following value:

Thus, the present study would claim that children of same-sex couples are “24% as likely” to graduate high school than children of opposite-sex couples. Clearly, this statement would be misleading.

This discussion should not be taken to mean that odds ratios are an inherently deceptive metric. Like any statistical measure, they can provide us with useful inferences when placed in appropriate context. But because the author fails to contextualize these metrics in the abstract, he provides a misleading picture of the results produced by the study.

I suspect that a defender of the study might attempt to save face by claiming:

These are all interesting criticisms, but none actually “debunk” the study. The fact remains that you don’t actually know whether selection bias (i.e. looking just at young adults currently living with their parents) compromised the results of the study: you’re just positing that it could be the case. You also claim that the author confusingly presents results in the abstract. But you fail to mention that, even when presented in their full context, the results of the study still clearly highlight lower graduation rates among children of same-sex couples than their opposite-sex counterparts. It’s clear that you’re just frantically searching for any reason to doubt the study because it calls into question your ideological priors.

Even if one (wrongfully, in my opinion) ignores the issue of selection bias and confusing presentation of results, the study still fails to support its key claims. It turns out that the “graduation rate” differences between children of same-sex couples and children of opposite-sex couples are rendered insignificant after controlling for whether the family has moved in the prior five years. I initially didn’t catch this fact because the author misleadingly states the following:

Table 8 in the appendix reports on another three logit regressions with the same dependent variable and the same right hand side variables, except for the variable used to control for family mobility—it uses the mobility measure ‘‘did child move within past 5 years.’’ There is no qualitative difference in the estimates when using the different mobility controls.

The author uses the phrase “no qualitative difference” to suggest to the reader that the results in the appendix simply mirror those presented in the body of the paper. But when you actually read the appendix, there are no longer statistically significant differences in “graduation rates” between children of same-sex couples and children of opposite-sex couples.

To clarify, this lack of statistical significance doesn’t necessarily imply that children in same-sex households fare equivalently to those in opposite-sex households. It does, however, call into question the robustness of the study’s conclusions.

To summarize then, the study’s conclusions about the efficacy of same-sex parenting are insufficient to reject the “no differences” hypothesis because:

The author’s focus on only young adults currently living with their parents ignores the bulk of young adults who go on to live in college dormitories, become independently employed, or enlist in the military.

The author’s presentation of odds ratios in the abstract is at odds (pun intended) with how odds ratios ought to be interpreted.

The author’s primary results are rendered insignificant after including controls for residential moves in the prior five years.

Sullins (2016a)

This study examines the relationship between same-sex parenting and the mental health of children as they enter adulthood. It leverages information regarding 20 children of same-sex couples identified by four waves of surveys administered via the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health). To ensure that identified children were actually children of same-sex couples, the author performs two verifications:

The parent of the child reported being in a marriage or marriage-like relationship with a partner of the same-sex during Wave I of Add Health.

The child corroborated that there was no opposite-sex parental figure in the household during Wave I of Add Health.

The author then models the relationship between same-sex parenting and depression risk during adulthood (as measured by the CES-D index), controlling for a variety of sociodemographic variables (e.g. parental educational attainment, household income). The model yields the following results:

The children with same-sex parents are 2.6 times more likely to experience depression by the fourth wave, after adjusting for demographic differences.

It would be easy to take this result at face value and assume they contradict the “no differences” hypothesis. However, Frank (2016) argues that we don’t know how long children in this study were raised by the same-sex couples in question. Because we lack this crucial information, we can’t attribute depressive risk to the parenting practices of same-sex couples with certainty.

To his credit, Sullins (2016b) responds to this objection. The author notes that Add Health asks respondents to report the number of years during which they lived with their parents. This information can then be used to model the relationship between same-sex parenting and depressive risk, controlling for length-of-time spent with the same-sex couple. This revised model purports to show that increased length-of-time spent with both same-sex parents is associated with increased depressive risk.

However, there are noticeable issues with the methodology used to obtain these results:

The revised model appears to drop nearly all of the sociodemographic variables that were included in the original model. No reasoning is provided for this decision.

The author makes the decision to group the length-of-time variable into four five-year categories. This is an odd choice because length-of-time is a continuous measure, not a categorical measure. In other words, there’s no reason to differentiate between being raised by a set of parents for 4.9 years vs 5.1 years. This oddity is compounded by the fact that the table doesn’t specify which length-of-time category the odds ratios correspond to. These metrics could be referencing the effect of living with one’s parents for 5-10 years, 10-15 years, or 15-20 years. The table simply doesn’t say.

The other (and arguably, more pressing) issue with this study is simply the low sample size. Even if the study was flawless in design, it would simply defy logic to allow a study of 20 children of same-sex couples to fully determine one’s opinion about the efficacy of same-sex parenting when there are plenty of other studies that examine outcomes among larger nationally representative samples of children in same-sex households. Thus, the study’s sample size and failure to appropriately control for length-of-time raised by a same-sex couple call into question the integrity of its results.

Mechanisms

Thus far, this essay has taken the approach of examining the “no differences” hypothesis purely through a statistical lens:

“Do the outcomes statistically significantly differ between household types?”

“Did the author control for the right variables?”

“Were same-sex parents accurately identified?”

While this approach has its merits, rigorous scientific analysis shouldn’t be limited to just bickering over statistical significance and effect sizes. It should also involve a discussion of the plausibility of the mechanisms underlying the phenomenon in question … so let’s have that discussion!

Those who reject the “no differences” hypothesis tend to provide the following three explanations for why children do best with a mother and father:

Complementarity: Men and women have, on average, different distributions of personality traits which, in turn, leads them to perform different household functions (e.g. taking care of children vs doing overtime at work). To ensure that children aren’t emotionally stunted, they need to have a mother and father that exemplify these complementary personality traits and their associated gender roles.

Evolutionary Advantage: Because humanity’s evolutionary instinct is to reproduce, human beings will naturally favor their own offspring. Thus, we should always expect parents to invest more in children who are biologically related to them relative to children who aren’t.

Instability: Because women are much more likely to initiate divorce than men, we would expect lesbian relationships to divorce at much higher rates than other types of relationships. This increased incidence of divorce would then negatively affect children because children whose parents undergo divorce experience worse mental health than children whose parents remain together.

Let’s explore each of these mechanisms in more detail.

Complementarity

One issue with the “complementarity” explanation is that it assumes most parental relationships consist of complementary personality traits when the phenomenon of assortative mating provides good reason to think just the opposite. To elaborate, assortative mating occurs when people enter relationships with others who are similar to them. This assortment can occur either because the individuals are in similar social environments (e.g. a PhD student meets her boyfriend in the same PhD program) or because the individuals have similar desires (e.g. a Catholic man wants to marry a Catholic woman). If assortative mating applies to people’s personalities, then most children would be growing up with parents who don’t have complementary personality traits, implying that complementarity probably isn’t that important in the grand scheme of things.

Also, the fact that same-sex couples are less likely (on average) to have complementary personality traits doesn’t imply that they’re less capable of dividing household functions. At the end of the day, someone in the couple has to cook dinner, do the laundry, and mow the lawn, so it’s inevitable that the couple will learn how to delegate these tasks amongst themselves. Same-sex couples might even divide household functions more advantageously than opposite-sex couples. If partners in a same-sex couple both learn how to do each household task (due to a lack of strict gender norms governing which tasks they’re “supposed” to do), then one member of the couple would be able to take care of the household by themselves when the other is unable to.

The last point to consider is that, in the limited set of cases where complementarity matters, same-sex parents can address this problem by having their children routinely interact with role models of the opposite sex (e.g. an aunt or uncle). In fact, this seems to be what gay couples do when raising a child whose sex is opposite to their own.

Thus, the “complementarity” explanation doesn’t provide sufficient reason to think of opposite-sex parents as superior to same-sex parents.

Evolutionary Advantage

The main issue with the “evolutionary advantage” explanation is that it fails to take into account the number of hoops that gay couples have to jump through to become parents. Because gay couples typically have to invest substantial effort into becoming a parent (via adoption or assisted reproductive technology), we have strong reason to think that these couples are highly dedicated to becoming parents. This statement is especially true when we think about gay parents in comparison to, say, straight couples who experience an unintended pregnancy.

A secondary issue is that there will always be children who end up in foster care/adoption centers because their biological parents were unable or unwilling to take care of them. Because every single couple - gay or straight - that seeks to adopt the child does not share a biological connection with the child, the “evolutionary advantage” explanation is simply meaningless in this context.

Lastly, even if we granted the importance of “evolutionary advantage”, it wouldn’t necessarily just apply to straight parents. It could also apply in cases where a sperm donor/surrogate is biologically related to a member of the couple in question. For example, if one partner in a lesbian couple has her brother donate sperm to fertilize an egg in the other partner’s womb, then both partners in the couple would ultimately share a biological connection to the child.

Thus, the “evolutionary advantage” explanation doesn’t provide sufficient reason to think opposite-sex parents are superior to same-sex parents.

Instability

The “instability” explanation is definitely the most plausible of the three mechanisms because a larger share of divorces are initiated by women than men. However, this explanation might be countervailed by another mechanism at play: the “double dose of motherhood” effect. Kabatek and Perales (2021) explain:

The comparative advantage observed for children in female same-sex-parented families may emerge because women’s parenting style tends to be more conducive to positive child development than men’s. This finding is consistent with Biblarz and Stacey’s (2010) review of the literature, in which they document that women score higher than men on parenting skills and develop warmer, closer, and more communicative relationships with their children. Similarly, compared with married heterosexual couples, female same-sex parents played more with their children and disciplined them less, and they were also less likely to use corporal punishment, set strict limits, or impose social and gender conformity on their children (Biblarz and Stacey 2010).

I can already anticipate skeptical readers hurriedly typing out a response to this point. “Doesn’t this argument imply that gay fathers are worse for children relative to lesbian and straight parents???” one might exclaim. However, this question betrays a misunderstanding of the mechanisms at play. Broadly speaking, we can consider various family forms as having certain trade-offs:

Thus, when all is said and done, no family structure is always going to come out on top since each has their own set of advantages and disadvantages. Importantly, the matrix above is not intended to be a full or even wholly accurate summary of all the mechanisms through which parenting can affect childhood outcomes. It simply illustrates the more fundamental point that, a priori, there’s no immediate reason to think that children raised by straight parents will be better off than children raised by gay/lesbian parents.

Conclusion

There are several conclusions that we can draw about the nature of same-sex parenting:

The best available studies find that, to the extent that there is any effect of same-sex parenting on children’s psychosocial wellbeing, the effects are likely to be small in magnitude (Bos et al 2016; Potter and Potter 2017; Calzo et al 2019; Mazrekaj, Fischer, and Bos 2022).

The best available studies find that same-sex parenting either has no effect or positive effects on children’s academic achievement (Boertien and Bernardi 2019; Mazrekaj, DeWitte, and Cabus 2020; Kabatek and Perales 2021).